Ralph Eugene Meatyard in COLLECTOR DAILY

October 25, 2023 - Loring Knoblauch

JTF (just the facts): A total of 33 black-and-white photographs, alternately framed in black/white and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space, the entry area, and the office.

Comments/Context: There are plenty of reasons why a photographer might decide to present his or her work as a series, sequence, or group rather than as a selection of single stand alone images. The larger thematic or subject matter commonalities among the pictures might make sense as a portfolio, grid, or typology. The images may have been conceived in a particular order, especially if they move chronologically through time from one image to the next. The photographer may be interested in creating a specific sense of narrative (linear or otherwise) that is derived from seeing the images together. Or he or she may actually be interested in the conceptual spaces (and possibilities) between the pictures, where the photographs provide a framework or scaffolding that is only partially filled in.

In the early 1970s, Ralph Eugene Meatyard worked on what would become his best known project, a series of 64 images gathered under the title “The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater”. The consistently unsettling Lucybelle Crater photographs all featured various friends and family members wearing masks and posing in pictures that would otherwise fit well into a family album. In particular, Meatyard’s wife often posed in a rubber witch mask with a big warty nose; other figures were generally seen in a transparent hard-plastic mask that allowed their own features to partially show through. Meatyard’s results (which were last shown in New York in 2018, reviewed here) found an uneasy balance between the mundanely predictable and the strangely surreal, the masks partially transforming people (and arranged scenes/relationships) that would otherwise have looked altogether familiar. Meatyard died in 1972, making the Lucybelle Crater photographs a kind of bookend to his artistic career.

This gallery exhibit steps back to the late 1960s, when Meatyard was experimenting with the series form, exploring ways he could create open-ended narrative impressions and situations. The show features three short series, each made up of six or seven photographs, where the images are hung together in ordered clusters. Knowing what we know about what would come later in the Lucybelle Crater series, the aesthetic seeds of that project are clearly alive in these shorter efforts, with Meatyard testing out combinations of masked figures, hats, and high contrast light and shadow options (both inside and out), which he remixed into various ephemeral scenarios.

Meatyard’s long term friendships with various writers and poets in Kentucky (including Wendell Berry, Guy Davenport, Thomas Merton and Jonathan Williams) likely amplified his interests in the contours and complexities of narrative, and all three of the series on view here leave the situations largely undefined, making room for alternate interpretations and storylines. “Bird in the Bush Infant Welfare Center” has two protagonists: a woman and a child, both wearing summer shorts and floppy white hats. Meatyard poses them inside a ruined house, having them flank sagging windows, peek through rotted holes in the walls and open doorways, and play improvised games on the stairs, atop a fallen door, and in the otherwise empty rooms. Using only the available light, the pictures are dark and shadowy, intermittently punctuated by a shaft of bright geometric light cast through a window. The photographs have a vaguely dusty Gothic mood (of a kind Francesca Woodman would employ a decade or so later), where innocent up-and-down creative play is surrounded by quiet premonitions of unease, the series offering different small episodes in a larger short story-like arc.

“Disabled Living Activity Group” is similarly mysterious, with a woman and child wearing masks and staged in a sparsely furnished echoing rooms. In several images, they tussle on the floor, perhaps wrestling, embracing, talking, or fighting, their masked faces interrupting our understanding of the moment. Other images feature the pair standing in the darkness, with reflections, shadows, and silhouettes amplified by intermittent brightness, the stained walls and muted quiet of the setups creating a charged atmosphere. The last series “American Cockroach and Blackbeetle Solvent Co.” is the most compositionally complex of the three, with as many as four figures arranged wearing various masks and floppy hats, both inside and outside on the porch and stairs. In these pictures, Meatyard seems to be deliberately upending obvious relationships, with adults and children intermingled and gathered into groups, in some cases, with just enough separation between the bodies to create implied friction or distance. Again, bright light comes in through windows, dark posts and window frames create insistent verticals, and enough is left narratively unsaid to allow for any number of imaginative interpretations. Seen as a group, the three series feel transitional in the best sense, with Meatyard testing and experimenting with ideas that haven’t yet entirely coalesced, but certainly feel promising.

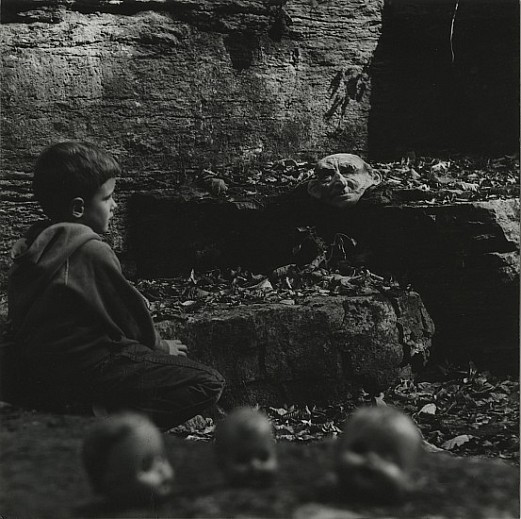

The rest of the show brings together nearly a dozen other Meatyard photographs from the 1960s, many employing masks, doll heads, and other haunting obscurity in one way or another. The scenes Meaytard crafts are nearly always filled with macabre undertones – a blurred figure with a mask stuffed into the nearby woodstove; a masked child playing the piano; a masked pair posed like a baseball catcher and umpire lingering in the long weeds; masked figures forming a triangle in a massive leaf pile; and another masked child hiding in a rustic bathroom with a urinal. Still other pictures step back from masks to probe other resonant moods and compositional structures, from a blurred silhouetted figure in a doorway surrounded by high contrast verticals to the matched pairing of a boy playing and a thin sapling.

The strongest of the images in this small show draw us into Meatyard’s dreamlike world, seducing us with unexpectedly strange and macabre situations. Few photographers since have

explored these spiritual netherworlds with such visual sophistication. Seeing the three series on view here is a particular treat, as they haven’t been shown or reproduced as often as many of Meatyard’s more famous projects. Placed between singular works from the 1960s and the Lucybelle Crater series of the early 1970s, they provide an important stylistic bridge, beginning to connect together a range of separate ideas into more layered narrative forms.

Collector’s POV: The individual Meatyard prints in this show are priced between $8500 and $28000 each, with the two prints by Ritchie at $3000 each; the three sets of prints by Meatyard are POR. Meatyard’s work is consistently available in the secondary markets, with a handful of lots coming up for sale every year. Prices for his vintage works have generally ranged between $2000 and $35000, with most under $10000; a few posthumous prints/portfolios were also made, and these prints have typically been sold for under $2000.

Download Article (PDF)Back to News