Roger Mayne in BLIND

March 1, 2023 - Colin Pantall

West London’s Working-Class

Roger Mayne’s pictures of London in the 1950s capture a city on the verge of change. In his images, you can see the destruction of the Second World War and the dullness of austerity mixing with the dynamism of migration and the rise of youth cultures. He shows a city that is alive, where the tarmac, the pavements, and the houses are part of a living culture that will come into full bloom in the decades to come.

Roger Mayne’s picture of the goalie in Brindley Road, Paddington, sums up the key themes of his work. This goalie is young, maybe 10 years old. He’s diving to his left, his mouth agape as his hand stretches down to block the ball, his fingers just a hair’s breadth away. His eyes are looking down in concentration, there is only one thing on his mind; he needs to save the ball. You can see his left foot, clad in a black rubber-toed plimsoll and grey school socks. The foot is grounded, giving him the impetus to fling his body across the tarmac.

And what tarmac it is. It’s rough, it’s scuffed, it’s potholed and ridden with gravel, gravel that will soon be embedded in the knees of the diving boy. It’s a picture that has an intensity about it, about the moment that goes beyond the moment. It has the dimension of time, and connects us to the life of the streets of London, to the theater of people who make their lives outside their homes.

The image is part of an exhibition titled What he saved for his family, now showing at The Gitterman Gallery in New York, with the majority of prints in the exhibition coming from Ann’s Box, a selection of prints that Mayne made for his wife Ann Jellicoe.

It’s a collection that exemplifies Mayne’s fascination with street life and invigorates the sometimes static ideas we have about British social history.

Optimism and life in a post-austerity age

In Mayne’s photographs of North Kensington, Paddington, and Petticoat Lane, we see optimism and life in a post-austerity age. The recent past had been one of economic hardship in which basic foodstuffs as well as luxury items such as sugar, cheese, and meats were rationed.

We see Mayne’s ‘Girl Jiving’ on Southam Street. It’s 1957 and she’s dancing in the street in an oversized single-breasted jacket with peak lapels over a diagonally striped t-shirt. It’s working class London in 1957 and she’s mixing 1930s fashion with a t-shirt, hair, and makeup that looked great then and look great now. It’s a picture both of its time and beyond its time, the blurry edge to it making the image extend beyond the three dimensions (and photographs always have three dimensions) of the frame.

That same year, in 1957, the British prime minister Harold Macmillan famously said, “Let us be frank about it: most of our people have never had it so good. Go round the country, go to the industrial towns, go to the farms and you will see a state of prosperity such as we have never had in my lifetime – nor indeed in the history of this country.”

“Empty, the streets have their own kind of beauty”

The jiving girl may have been living her best life, but this wasn’t peak prosperity for her. The street she lived on was the most densely populated street in London (according to a 1961 survey), a place where children played in the streets because there were no green spaces available. The cholera epidemics and 40-year life expectancies may have been things of the past, but poverty and overcrowding were not.

Mayne’s pictures also show the changes these communities are going through.

Roger Mayne didn’t foreground this poverty. He photographed Southam Street in a way that was in some ways nostalgic. He wrote, “Empty, the streets have their own kind of beauty, a kind of decaying always great atmosphere… My reason for photographing the love on them, and the life on them. . . . [I]t may be warm and friendly on a sunny spring weekend when the street is swarming with children playing.”

At the same time, he doesn’t avoid the signs of poverty, the indicators of decay, and nor does he romanticise them. When brickwork crumbles, you know it is a sign of neglect and not some kind of shabby working-class chic. His pictures also show the changes these communities are going through. Stephen Brooke wrote that the immediacy of Mayne’s images helped him “capture the dynamism of working-class life and chronicle new actors on the urban stage such as teenagers and African and West Indian immigrants.”

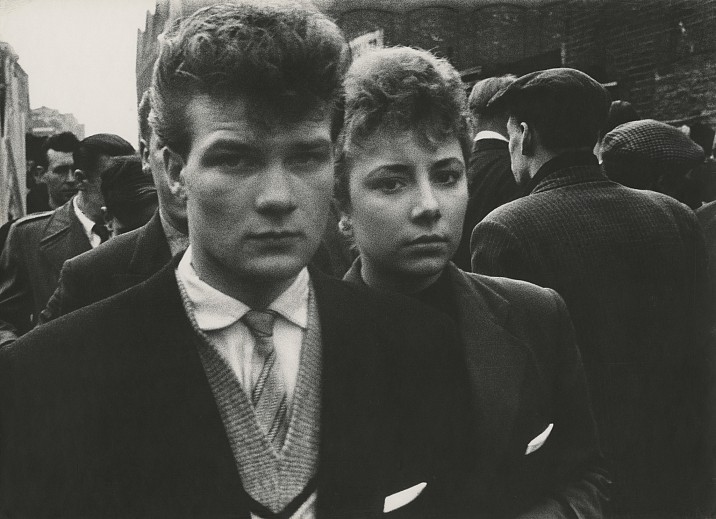

So along with the jiving girl, we see Teddy Boys and Teddy Girls in Petticoat Lane. The look the Teddy Boy gives Mayne as he points his camera at him is not welcoming. We see a pair of girls standing at Battersea Funfair in oversized jackets, hair curled, shirts knotted at the waist, one with a Victorian cameo pinned to her shirt collar, the past wrapped into the present.

The past is blended with the present

The changing demographics of the city are shown in examples of Mayne’s pictures of West Indians coming to the city; two small boys stand in the street in their primary school shorts and sandals as the world passes around them. Another picture shows two dark-skinned women shaking hands, with the kind of style that possibly comes more easily to Italians than the English. These are streets where women socialize, where children’s games rule, where everyone mixes, albeit sometimes uneasily.

Roger Mayne has something in common with Helen Levitt

In other words, it’s a world. It develops, it changes, it shifts, but it lives on the streets. In this, Mayne has something in common with Helen Levitt, whose work in New York framed the city as a child’s playground where doorways, windows, and tenement steps announced the players’ entrances and exits, where human activity has gone beyond planning and transformed space into place with multiple functions and identities.

The same is true in Roger Mayne’s work. People play cards on the curb, they gather in groups, they cry their tears, they watch the world passing by, they are the world passing by. It’s a world that is public rather than private, where class is performed on the streets, where to play in the streets was a marker of your class, your affluence, and the possibilities life held for you.

It’s a world that is nostalgic in some ways, but is also a reminder of what we have lost. The public sites Mayne photographed, the spaces of the street, have been taken over by cars or commodified and securitized. And when we wonder at the nostalgia of it all, it might be a nostalgia tinged with mourning, not at what we have lost in our striving for affluence but at what has been taken from us.

In Mayne’s pictures, the past is blended with the present, and the present looks to the future. Mayne’s pictures are not just memories of an idealized past, but markers of the present. His images are filled with the imagination of the people he photographed, people who are now either old or dead, but who connect to anyone young now who seeks to live at least part of their lives outside the comfort of their homes, phones, and laptops.

Back to News