DEAR DAVE 26

January 27, 2018 - Charles H. Traub

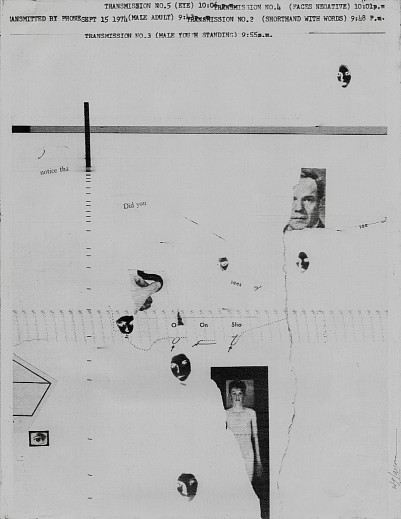

Fireflies: Fax Machine Images

On WILLIAM LARSON by CHARLES H. TRAUB

DEAR DAVE 26

After 40 years, I’m still in awe of William Larson’s Firefly images. I first encountered them in 1977 when I began working on a chronicle of photography at the Institute of Design (ID) in Chicago, The New Vision: Forty Years of Photography. Larson’s faxed images became a quintessential and exemplary art of my traveling exhibition that originated at the Light Gallery in 1979 and in the subsequent book, published by Aperture in 1982. How time flies!

Fireflies in themselves are light in motion. Catching them is about timing (a quick hand) and image making is about all three—time, light and motion. In a single transmission, William Larson caught something new about this relationship that hadn’t been seen before in six-minute transmissions of collaged and montaged images using a Graphic Sciences DEX 1 Teleprinter in 1969. He sent his imagination flying into a new world of transmission.

This optical printer transformed an image into sound, and in its transmission sound back into image. A spark was produced by a stylus burning the image into carbon paper, hence the title—Fireflies. For any communicator, the potential of such a machine was awesome in 1969 when Larson first started experimenting with it. In six minutes you could send an image to almost any remote source with a compatible machine. Wow, that was fast! Almost unbelievable, but it was the foundation of transmitting images in the realm of the circuit. Larson had vision: today we can send a high definition image in less than six milliseconds over the internet. Larson, like the rest of us is probably still impatient waiting for that fraction of time as the modem flickers like the firefly, and both have a bit short but a glowing life. Time really flies, and old technology crashes while new technology soars in its place.

Image-making has always involved technology. The Institute of Design carried forth Moholy-Nagy’s vision and the Bauhaus Legacy and the idea that human creativity was extended through the implementation and experimentation with technology itself. In the book, The New Vision, William Larson’s image from Fireflies was notated with the following quote:

The enemy of photography is the convention. The salvation of photography comes from the experimenter who dares to call “photography” all the results which can be achieved with photographic means with camera or without. - László Moholy-Nagy

William Larson had just graduated from the ID in 1968 and a year later when I entered the school, as a graduate student, he was already celebrated. He was held up along with Keith Smith, Barbara Blondeau and Thomas Barrow as a new generation of artists, pushing the boundaries of photographic practice through any means that could transform light into art. The innovative spirit of the ID, following the Bauhaus Legacy, was spread in colleges and universities throughout the country in the 1970s. The mantra was, find out what can be said with an optical device as an extension of human being to light the fireflies in us all.

So what of the Fireflies images themselves? In first examining them we might assume they were made yesterday, on a computer and an inkjet printer. They look so contemporary. They are not facsimiles of reality or indexical copies but rather traces of time, motion and light, with the added component that they were produced using sound. As Moholy-Nagy said in 1947:

Optophonetic art will allow us to see music, hear pictures simultaneously: a startling articulation of space-time.

In the realm of the circuit, everything is reduced to zeros and ones—music, text, image—still or moving, or raw data itself, or a combination of all of these forms. We take it all for granted, but we also realize that the computer is the great leveler, the democratizing integrator of ideas from any and all disciplines. The Firefly collages, montages, transmissions—whatever you want to call them—are symbolically anticipating the abstract, or existential connection, that electronic data has to offer—a precursor of our current age of data. Larson’s pictures are playful mementoes, nostalgic reflections and random gestures, but demanding us to bring our own creativity to such activity—they are Moholy-Nagy like, but not.

Potentially the field of visual expression has immensely expanded through science and technology ... the new possibilities of expressions are dependent for their realization upon a high standard of knowledge of light and electricity - László Moholy-Nagy