Jackie Robinson and the Color Line

Jackie Robinson and the Color Line is an exhibition of the collection of Paul Reiferson, that uses photographs and artifacts to vividly narrate the story of baseball’s journey toward integration.

Jackie Robinson, a trailblazing figure in civil rights, shattered baseball’s color line when Martin Luther King Jr. was still in college, earning praise from King as “a sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.” The exhibition frames Robinson’s odyssey within a larger one that had begun sixty years earlier, when men like Fleet and Weldy Walker, Sol White, Robert Higgins, and Javan Emory played for integrated teams in the late 19th century.

The visual history of the Negro Leagues is marked by absence: black newspapers, lacking large photography staffs, rarely shot games, and white newspapers saw little profit in it. When black players approached or crossed the boundary into the white world, however, they became more visible. Inspired by this insight, this collection of photographs, complemented by significant objects offering context, directs its focus to narratives situated proximate to the color line, communicating both the forward-flowing hopes of integration and the undertow of racism and, in no modest measure, derives its impact from these competing currents.

This collection of over 60 objects has been meticulously curated over more than a quarter century and spans the years 1885-1955. The endpoint was chosen because it coincides with the beginning of the modern civil rights movement and Martin Luther King Jr.’s activism, to which the long challenge to baseball’s color line serves as a prologue acknowledged by King himself.

Please note: The word “Negro” appears several times throughout this exhibition. Historically, this term was used to denote persons of Black African ancestry. Although some people utilized it to promote positive Black identity in the mid-20th century, it began to take on increasingly negative connotations during the American civil rights movement. We use it only in reference to the Negro Leagues, as those institutions were known at the time, and when citing historically significant quotes.

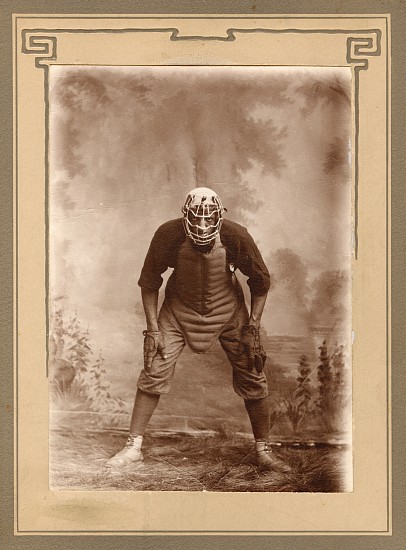

Blacks made significant strides in achieving civil rights after the Civil War, and it was not unusual for a northern white team to include a black player. More often than not, the black player was the catcher, as catcher’s gloves and chest protectors were only beginning to be widely used and the short supply of good catchers created opportunities. While the National League was not integrated, competing leagues such as the International League and the American Association allowed several black players.

A turning point was a landmark Supreme Court decision in 1883 that struck down the critical provision in the Civil Rights Act of 1875 prohibiting racial discrimination in public places. The decision essentially legalized the idea of “separate but equal,” only using different language. Separation led ineluctably to increasing racism and to the drawing of the color line.

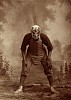

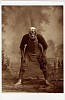

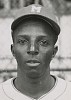

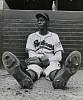

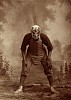

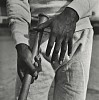

Unidentified photographer, Javan Emory, c. 1885

Vintage gelatin silver print, 6 1/16 x 4 3/8 in. (15.4 x 11.1 cm)

Mounted.

8489

Exhibited: Who Shot Sports: A Photographic History, 1843 to the Present. Brooklyn Museum, 07/15/2016 to 01/08/2017. Tampa Museum of Art, 02/05/2017 to 04/30/2017. Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, 05/25/2017 to 10/19/2017. Allentown Art Museum, 05/04/2018 to 07/29/2018. The Annenberg Space for Photography, 10/13/2018 to 01/25/2019.

Legend has it that it was because of Javan Emory's extraordinary skills as a ball player that the color line was drawn by the National League. This is the only extant image of Emory and one of two known prints, this example being the finest.

Since its discovery near Philadelphia a generation ago, this image continues to raise a central question: why was this black man presented so powerfully—in equipment many young white men could not afford and in the standard pose of the tough catcher they aspired to be—when the most widely seen images of black baseball at the time, circa 1885, were racist lithographs with catchers wearing birdcages as masks?

Only recently did we learn the answer: the subject, Javan Emory, was not just any catcher. In an obituary published in 1923, the claim was made that Emory actually crossed the color line and played for Boston in the National League; at the time the obituary was published, Jackie Robinson was five years old. Other newspaper accounts of Emory make a further claim:

TERRIFIC BATTING OF THE LOCAL MAN HELD DIRE RESULTS FOR HIS RACE

Javan Emory, the well known head waiter at the Mansion House, has the credit of sealing the fate of the negro ball player so far as the National League is concerned. Just because Mr. Emory put his eagle eye on the ball, and proceeded to bat the cover off in a game between Boston and Toronto, the ban was placed on the colored man by the senior major league.

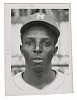

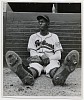

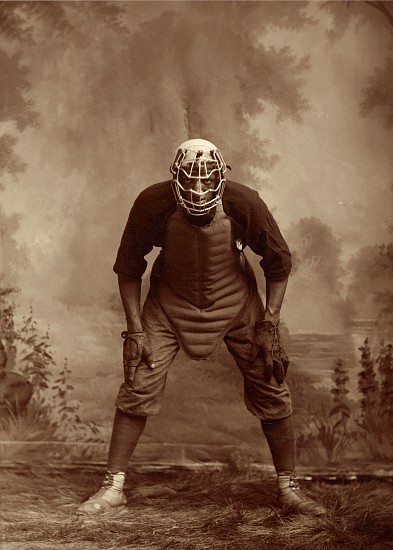

Unidentified photographer, Javan Emory, c. 1885

Pigment print; printed later, 15 1/16 x 10 3/4 in. (38.3 x 27.3 cm)

8506

Legend has it that it was because of Javan Emory's extraordinary skills as a ball player that the color line was drawn by the National League. This is the only extant image of Emory and one of two known prints, this example being the finest.

Since its discovery near Philadelphia a generation ago, this image continues to raise a central question: why was this black man presented so powerfully—in equipment many young white men could not afford and in the standard pose of the tough catcher they aspired to be—when the most widely seen images of black baseball at the time, circa 1885, were racist lithographs with catchers wearing birdcages as masks?

Only recently did we learn the answer: the subject, Javan Emory, was not just any catcher. In an obituary published in 1923, the claim was made that Emory actually crossed the color line and played for Boston in the National League; at the time the obituary was published, Jackie Robinson was five years old. Other newspaper accounts of Emory make a further claim:

TERRIFIC BATTING OF THE LOCAL MAN HELD DIRE RESULTS FOR HIS RACE

Javan Emory, the well known head waiter at the Mansion House, has the credit of sealing the fate of the negro ball player so far as the National League is concerned. Just because Mr. Emory put his eagle eye on the ball, and proceeded to bat the cover off in a game between Boston and Toronto, the ban was placed on the colored man by the senior major league.

LINK to Paul Reiferson's essay "He Wears the Mask" in Southwest Review, November 3, 2015

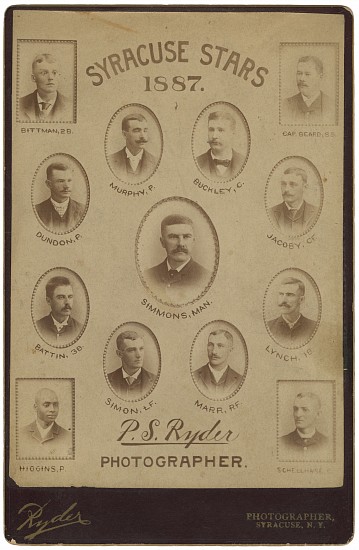

Philip S. Ryder, Syracuse Stars, 1887, July

Vintage albumen print, 5 11/16 x 4 in. (14.4 x 10.2 cm)

Cabinet card. Mount 6 7/16 x 4 3/16 in.

8472

Robert Higgins, pitcher, was one of the last black players to play professional baseball on an integrated team until Jackie Robinson, almost sixty years later.

Manager Simmons ordered the Syracuse Stars to report at eleven o’clock on a Sunday morning to the studio operated by P. S. Ryder, who was also a club shareholder, to have a team portrait made, but two of Higgins’s teammates refused to be photographed with him. Ryder produced this composite in lieu of a team photograph.

The Syracuse Evening Herald reported:

“Neither Pitcher Crothers nor Left Fielder Simon reported at the hour named…It was said among the players that these men objected to having their pictures taken with the colored pitcher, Higgins. It was understood that Simon was following the lead of Crothers…He gives as his reason for not appearing at the photograph gallery that as a Southern born man he could not consent to have his picture taken in a group with Higgins, a negro. He was not willing to appear in a picture with him, but did not object to playing with him. None of the other players in the team seems to be opposed to Higgins. He is a quiet, respectful, gentlemanly young fellow, and when his trouble came about and he saw that there was a feeling against his color, he went to the Washington House where he boards, and cried like a child.”

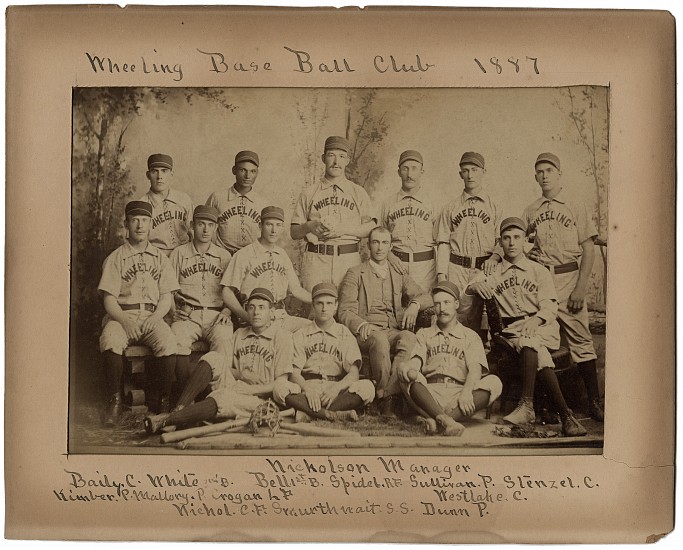

Parsons Studio, Wheeling Base Ball Club, 1887

Vintage albumen print, 6 x 8 13/16 in. (15.2 x 22.4 cm)

Imperial cabinet card. Mount 6 7/8 x 9 13/16 in.

With original 8 x 10 in. window mat cut to 5 1/2 x 8 in. window.

Titled and identifications in ink on mat recto.

Photographer's studio name, "IMPERIAL" and "WHEELING W VA" printed on card recto.

8473

Sol White, one of the black players banned in 1887 despite being one of the league’s best hitters, is pictured in one of the few surviving photographs of him.

White joined the Wheelings of the Ohio State League in 1887 and batted .370. Nevertheless, he was banned, together with all of the league's black players, during the off-season. The ban was temporarily rescinded a few weeks after Weldy Walker, a black catcher in the league, wrote an open letter to the league president in Sporting Life. White rejoined Wheeling, but a new manager refused to play him, and he was released.

White went on to play for prominent segregated teams and, in 1907, published History of Colored Base Ball. Without White's book, much of the history of the early black game would be lost, together with important insights about the color line from the perspective of black players.

White was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

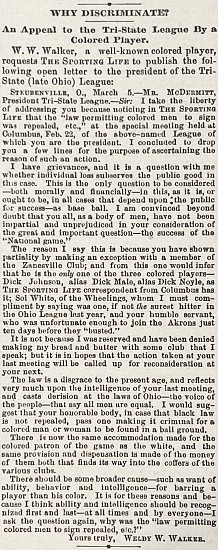

"Why Discriminate?" An Open Letter from Weldy Walker, March 14, 1888

Newspaper

Original bound volume of Sporting Life, April 13, 1887–April 4, 1888.

8544

When the Tri-State League banned black ballplayers, Weldy Walker sent a letter to the league’s president and to the editor of Sporting Life stating his grievances. Among his arguments, Walker notes that Sol White, of the Wheelings, "was one, if not the surest hitter in the Ohio League last year."

While many athletes, including Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and Colin Kaepernick, have spoken passionately for racial justice, Weldy Walker’s letter might be the first such statement, and it remains one of the most eloquent.

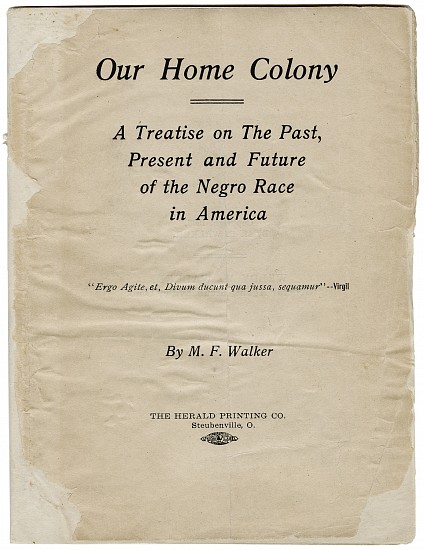

Moses Fleetwood Walker, Our Home Colony, 1908

book, 6 5/8 x 5 in. (16.8 x 12.7 cm)

A Treatise on The Past, Present and Future of the Negro Race in America.

The Herald Printing Co., 1908, first edition, quarto, in original stapled wrapper, 47 pp.

8519

After leaving baseball, Moses Fleetwood (Fleet) Walker, explored the idea of black Americans emigrating to Africa as a last resort option after the Supreme Court’s decisions in the 1883 civil rights cases reinforced racial segregation. After a generation of segregation and violence, Walker no longer saw any foundation for "a hope that the lot of the American Negro will grow better," and, as a result, he saw no alternative to mass resettlement in Liberia.

Fleet Walker, Weldy Walker's brother, became the first man to cross the color line on May 1, 1884 when he caught barehanded for Toledo of the American Association, then considered a major league. He was released at the end of the season because of injury, but the animus of some white opponents also played a role.

During an exhibition game between Toledo and Chicago in August 1883, Cap Anson, one of the most popular players of his era, objected to taking the field against Walker. Told his team would forfeit their share of the gate receipts, Anson replied, "We'll play this here game, but won't play never more with the n***** in." Because of Anson's popularity, this incident was widely discussed, and it is generally seen as the beginning of the end of integrated baseball.

This is the only copy of Walker's pamphlet in private hands; the only other known example is in the collection of the University of Michigan, which Walker attended.

“In no other profession has the color line been drawn more rigidly than in base ball,” wrote Sol White in his History of Colored Base Ball (1907).

In this context, one particularly searing moment reveals itself in hindsight to have been a turning point: in 1903, a black catcher named Charles Thomas, a student at Ohio Wesleyan, was traveling with coach Branch Rickey to play in South Bend, Indiana. Two matching photographs in the collection, one saved by Thomas and the other by Rickey, help tell the story. Rickey spoke publicly about the lasting effect of this experience at a Rotary Club luncheon in April 1945, four months before his first contact with Jackie Robinson; Robinson himself shared the story in his autobiography.

Sol White wrote of preliminary plans to get someone across the color line: first, of Baltimore manager John McGraw’s scheme to sign Charlie Grant by passing him off as Native American, which McGraw accomplished, only to have the ruse detected immediately; and second, of the Boston Braves wanting to sign William Clarence Matthews, who had just graduated from Harvard. Both Grant and Matthews are pictured here. “In no other profession has the color line been drawn more rigidly than in base ball,” wrote Sol White in his History of Colored Base Ball (1907). Both the virulent racism of this period and the angry reaction to it can be seen through several objects.

Charles A. Buss, Page Fence Giants, Charlie Grant, 1897-1898

Vintage gelatin silver print, 7 9/16 x 9 1/4 in. (19.2 x 23.5 cm)

Mounted on board 8 1/8 x 9 15/16 in.

Photographer's Jefferson, WIS stamp and "Sherman Barton, Normal, Ills" in ink on mount verso.

8471

Charlie Grant, standing second from left, almost crossed the color line in 1901. Sol White told his story in his book History of Colored Base Ball (1907).

While Manager [John] McGraw [of the American League's Baltimore Orioles] was in Hot Springs, Ark., preparing to enter the season of 1901, he was attracted toward Chas. Grant....With the color line so rigidly enforced in the American League, McGraw was at a loss as to how he could get Grant for his Baltimore bunch. [McGraw] conceived the idea of introducing Grant in the league as a Native American. Had it not been for friends of Grant being so eager to show their esteem while the Baltimores were playing in Chicago, McGraw's little scheme would have worked nicely. As it was, the bouquet tendered to Grant, which was meant as a gift for the colored man, was really his undoing. McGraw was immediately notified to release Grant at once, as colored players would not be tolerated in the league.

LINK to more on Charlie Grant.

Unidentified photographer, Ohio Wesleyan Baseball Team [Branch Rickey and Charles Thomas], 1903

Vintage gelatin silver print, 6 9/16 x 8 1/2 in. (16.7 x 21.6 cm)

Mounted to 9 16/16 x 11 15/16 in.

Provenance: Charles Thomas

8474

In 1903, Charles Thomas (second row, third from left) faced an act of discrimination so searing that it haunted Branch Rickey (top row, left), then the baseball coach at Ohio Wesleyan, and inspired him to be instrumental in dismantling the color line in Major League Baseball.

"From the first day at Ohio Wesleyan," catcher Charles Thomas later recalled, "Branch Rickey took a special interest in my welfare." In May 1903, the team traveled to South Bend, Indiana, to play Notre Dame. The Oliver Hotel, where the team had reservations, refused to allow Thomas to lodge. Rickey convinced the hotel manager to place a cot in his room for Thomas to sleep on, as they would do for a black servant. That night Thomas wept and rubbed his hands as if trying to rub off the color. "Black skin! Black skin!" he said to Rickey. "If only I could make them white."

"That scene haunted me for many years," explained Rickey, "and I vowed that I would always do whatever I could to see that other Americans did not have to face the bitter humiliation that was heaped upon Charles Thomas."

Branch Rickey told Jackie Robinson that he integrated baseball for Charles Thomas. Robinson himself recounted this story in his autobiography, I Never Had it Made. As Robinson wrote, “Thirty-five [sic] years later, while I was lying awake nights, frustrated, unable to see a future, Mr. Rickey, by now the president of the Dodgers, was also lying awake at night, trying to make up his mind about a new experiment. He had never forgotten the agony of that black athlete.”

The collection includes the only two known prints in private hands of this 1903 image—one that belonged to Charles Thomas and the other to Branch Rickey.

A scene in the movie 42 was invented to introduce the true story of Charles Thomas. [see link HERE]

Unidentified photographer, Ohio Wesleyan Baseball Team [Branch Rickey and Charles Thomas], 1903

Vintage gelatin silver print, 6 9/16 x 8 1/2 in. (16.7 x 21.6 cm)

Mounted to 9 x 12 in.

Provenance: Branch Rickey; by descent to his grandson.

8505

In 1903, Charles Thomas (second row, third from left) faced an act of discrimination so searing that it haunted Branch Rickey (top row, left), then the baseball coach at Ohio Wesleyan, and inspired him to be instrumental in dismantling the color line in Major League Baseball.

"From the first day at Ohio Wesleyan," catcher Charles Thomas later recalled, "Branch Rickey took a special interest in my welfare." In May 1903, the team traveled to South Bend, Indiana, to play Notre Dame. The Oliver Hotel, where the team had reservations, refused to allow Thomas to lodge. Rickey convinced the hotel manager to place a cot in his room for Thomas to sleep on, as they would do for a black servant. That night Thomas wept and rubbed his hands as if trying to rub off the color. "Black skin! Black skin!" he said to Rickey. "If only I could make them white."

"That scene haunted me for many years," explained Rickey, "and I vowed that I would always do whatever I could to see that other Americans did not have to face the bitter humiliation that was heaped upon Charles Thomas."

Branch Rickey told Jackie Robinson that he integrated baseball for Charles Thomas. Robinson himself recounted this story in his autobiography, I Never Had it Made. As Robinson wrote, “Thirty-five [sic] years later, while I was lying awake nights, frustrated, unable to see a future, Mr. Rickey, by now the president of the Dodgers, was also lying awake at night, trying to make up his mind about a new experiment. He had never forgotten the agony of that black athlete.”

The collection includes the only two known prints in private hands of this 1903 image—one that belonged to Charles Thomas and the other to Branch Rickey.

A scene in the movie 42 was invented to introduce the true story of Charles Thomas. [see link HERE]

Unidentified photographer, Harvard Baseball Team [William Clarence Matthews], 1905

Vintage gelatin silver print, 10 1/16 x 13 5/16 in. (25.6 x 33.8 cm)

Mounted to 11 1/4 x 13 7/8 in.

8497

William Clarence Matthews, of Harvard, was considered as a candidate to be the first to cross the color line.

Sol White informed the readers of his History of Colored Base Ball in 1907 that, "[i]t is said on good authority that one of the leading players and a manager of the National League [Fred Tenney of the Boston Nationals] is advocating the entrance of colored players in the National League with a view of signing '[William Clarence] Matthews,' late of Harvard. It is not expected that he will succeed in this advocacy of such a move, but when such actions come to notice there are grounds for hoping that some day the bar will drop and some good man will be chosen from out of the colored profession that will be a credit to all, and pave the way for others to follow."

Two years earlier, Matthews had raged against the color line to a reporter from the Boston Evening Traveler: "I think it's an outrage that colored men are discriminated against in the big leagues. What a shame it is that black men are barred forever from participating in the national game. I should think that Americans should rise up in revolt against such a condition. Many negroes are brilliant players and should not be shut out because their skin is black."

Matthews went on to become one of the first black district attorneys in the country.

The collection contains several objects not pictured and not on display in the exhibition, including a Dark Town Battery mechanical bank (c. 1888), The Funny Game of Hit or Miss, a McLoughlin Bros. board game based on a carnival attraction in which black men served as targets for thrown baseballs (c. 1901), two baseballs used for this purpose stamped African Dodger (c. 1900-1925), and a Stall & Dean equipment catalog advertising a line of black-colored gloves titled The N***** Line of Gloves and Mitts (1911).

These objects provide context regarding the virulent racism of the time and the difficulty any athlete would have encountered crossing the color line. They are not pictured, however, so as not to risk their misuse.

The Negro Leagues produced many legendary players, including Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, and Smokey Joe Williams. The visual history of these times, however, is characterized by absence; there are likely more surviving images of Babe Ruth during the 1920s and 1930s than there are images of every player in the Negro Leagues combined, excluding team photos.

If any player in the Negro Leagues deserved to cross the color line first, it was Satchel Paige, who made his professional debut in 1926 and became one of the greatest pitchers of all time and a figure in the black community more popular than Joe Louis, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, or Langston Hughes, none of whom had, as a Paige biographer put it, "Satchel's over-the-top style and charm." The same rule-flouting and fun-loving qualities and showy rebelliousness that made Paige a hero to fans made him a loose cannon to team owners rather than the exemplary public figure they believed they needed, and found, in Jackie Robinson.

George Strock, Satchel Paige in Harlem, 1941

Vintage gelatin silver print, 10 3/4 x 10 1/4 in. (27.3 x 26 cm)

Annotated: "Satch an idol among negro kids all over country. Harlem school kids mob him here" in pencil, with photographer's credit stamp and Time/Life credit and file stamps in ink verso.

Illustrated: Life, June 2, 1941, p. 92 [using this print] and Fall 1991.

5727

Exhibited: Who Shot Sports: A Photographic History, 1843 to the Present. Brooklyn Museum, 07/15/2016 to 01/08/2017. Tampa Museum of Art, 02/05/2017 to 04/30/2017. Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, 05/25/2017 to 10/19/2017. Allentown Art Museum, 05/04/2018 to 07/29/2018. The Annenberg Space for Photography, 10/13/2018 to 01/25/2019.

George Strock’s photographic essay for Life depicts Satchel Paige’s larger-than-life persona. The same qualities that made Paige a hero to fans made him questionable to Major League team owners.

Life sent George Strock to photograph Paige for an article titled "Satchel Paige, Negro Ballplayer, Is One of the Best Pitchers in the Game.” These photographs were shot four years before Life’s photographic essay on Jackie Robinson, the difference is both startling and instructive.

Robinson's image was carefully controlled. Paige, by contrast, allowed himself to be photographed in a Harlem pool hall in a stylish suit. Paige was cultivating the image that made him a beloved figure in the black community. He did not appreciate how the same image would be misperceived outside that community. Strock’s images and the magazine's captions telegraphed that Paige was too large and independent a personality to be the first to cross the color line.

LINK to Life, June 2, 1941, pp. 90-2

George Strock, Satchel Playing Boogie Woogie in Black Yankee (Harlem) Club, 1941

Vintage gelatin silver print, 10 5/8 x 10 3/8 in. (27 x 26.4 cm)

Titled and annotated in pencil with photographer's credit stamp and Time/Life credit and file stamps in ink verso.

Illustrated: Life, June 2, 1941, p. 92 [using this print].

8480

Life sent George Strock to photograph Paige for an article titled "Satchel Paige, Negro Ballplayer, Is One of the Best Pitchers in the Game.” These photographs were shot four years before Life's photographic essay on Jackie Robinson, the difference is both startling and instructive.

Robinson's image was carefully controlled. Paige, by contrast, allowed himself to be photographed in a Harlem pool hall in a stylish suit. Paige was cultivating the image that made him a beloved figure in the black community. He did not appreciate how the same image would be misperceived outside that community. Strock’s images and the magazine's captions telegraphed that Paige was too large and independent a personality to be the first to cross the color line.

Life's sarcastic caption read: "Satchel plays some boogie woogie on the piano for the Black Yankees. His playing shows more gusto than polish and considerably less talent than his baseball playing." Despite the caption, no other photograph captures Negro League baseball in the afterglow of the Harlem Renaissance like this one.

LINK to Life, June 2, 1941, pp. 90-2

George Strock, Satchel Paige Playing Pool. NY, NY, 1941

Vintage gelatin silver print, 10 3/4 x 10 3/8 in. (27.3 x 26.4 cm)

Annotated "Satch, only a fair pool player, usually loses more than he wins. Flat feet?" in pencil, with photographer's credit stamp and Time/Life credit and file stamps in ink verso.

Illustrated: Life, June 2, 1941, p. 92 [using this print].

5728

Life sent George Strock to photograph Paige for an article titled "Satchel Paige, Negro Ballplayer, Is One of the Best Pitchers in the Game.” These photographs were shot four years before Life's photographic essay on Jackie Robinson, the difference is both startling and instructive.

Robinson's image was carefully controlled. Paige, by contrast, allowed himself to be photographed in a Harlem pool hall in a stylish suit. Paige was cultivating the image that made him a beloved figure in the black community. He did not appreciate how the same image would be misperceived outside that community. Strock’s images and the magazine's captions telegraphed that Paige was too large and independent a personality to be the first to cross the color line.

LINK to Life, June 2, 1941, pp. 90-2

George Strock, Satchel warms up before the game. His uniform resembles the Yankees' outfit, 1941

Vintage gelatin silver print, 13 7/16 x 10 1/2 in. (34.1 x 26.7 cm)

Mounted on board; annotated in ink and stamped and dated by Time and LIFE on mount verso. (Similar stamps and annotations probably on print verso but only a fraction can be seen because of print lifting off mount at bottom.)

Illustrated: Life, June 2, 1941, p. 90 [using this print].

8498

The New York Black Yankees played at Yankee Stadium and had uniforms that closely mimicked those of the white club, providing this image with poignancy as Paige is so close to the Major Leagues, superficially, and yet so far away. That understanding echoes the language of the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate facilities are inherently unequal.”

In 1952-54, in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially segregated public schools were inherently unequal and violated the Constitution.

Life sent George Strock to photograph Paige for an article titled "Satchel Paige, Negro Ballplayer, Is One of the Best Pitchers in the Game.” Shot four years before Life's photographic essay on Jackie Robinson, the difference is both startling and instructive. [see other images of Paige]

LINK to Life, June 2, 1941, pp. 90-2

The experiences of white and black men serving in the armed forces during World War II served to soften attitudes towards integration.

On August 24, 1945, Branch Rickey sent scout Clyde Sukeforth to Chicago to make the first contact with Jackie Robinson, then with the Kansas City Monarchs. Four days later, Sukeforth and Robinson traveled to New York to meet with Rickey, a seminal moment in the histories of both baseball and civil rights. It was at this meeting that Rickey convinced Robinson of the necessity to “turn the other cheek” for the experiment to be successful, and Robinson signed a contract that day—since lost—crossing the color line for the first time since 1889.

Branch Rickey’s original strategy was to sign several black players for Dodgers minor league teams and announce them all at once. A contract with Don Newcombe, signed eight days before Robinson signed with Montreal, was part of this strategy. But Rickey’s hand was forced by a forthcoming city government report calling for integration and mentioning that signings were imminent. Fearing the announcement of Robinson’s signing would then appear to have been influenced from outside, Rickey asked for the report to be postponed and ordered Robinson to fly to Montreal to sign a contract.

In addition to Don Newcombe, the original announcement was likely intended to include Johnny Wright, Roy Campanella, and Roy Partlow; all signed directly with Dodgers affiliates in the months after Robinson.

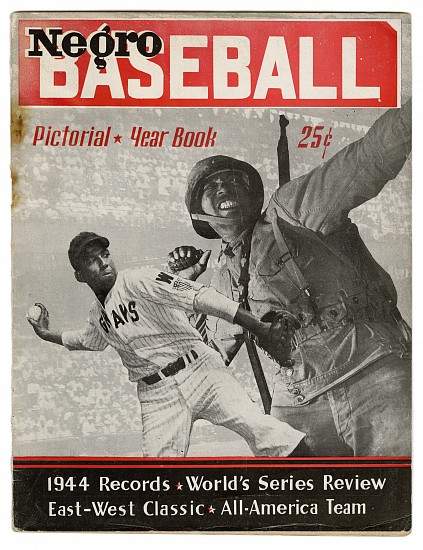

Negro Baseball Pictorial Year Book, 1944

Magazine, 11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

Original pictorial wrappers.

8517

The cover image depicts Homestead Grays pitcher Ernest “Spoon” Carter and a grenade-throwing soldier in identical poses. The imagery is as obvious as it is compelling.

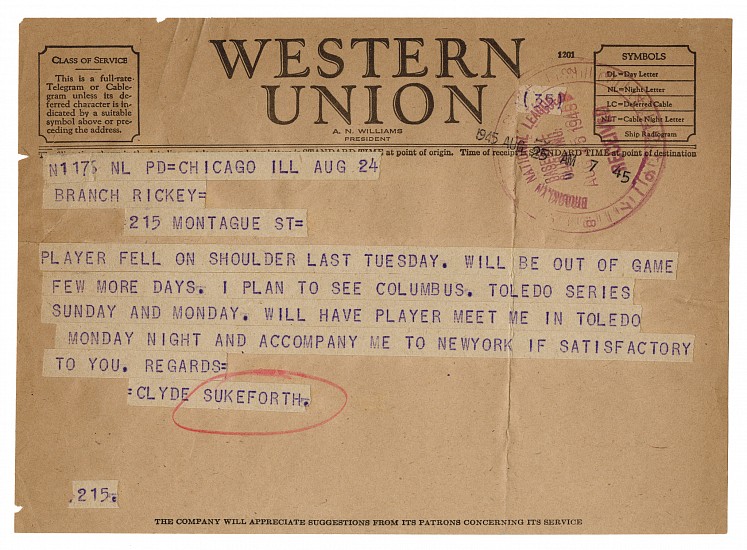

Telegram from Clyde Sukeforth to Branch Rickey establishing first contact with Jackie Robinson and arranging first meeting between Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey, August 24, 1945

5 3/4 x 8 in. (14.6 x 20.3 cm)

Provenance: Branch Rickey; by descent to his grandson.

8509

It would be difficult to overstate the historical significance of these two telegrams (see next object), as they are the only surviving objects related directly to the events of August 1945. The first establishes that contact with Robinson had been made by the Dodgers organization and arranged for the historic meeting between Robinson and Rickey; the best explanation for the second is that it sets forth a plan to get Robinson to sign his color-line crossing contract that day.

On August 24, 1945, Sukeforth made first contact with Robinson while he was with the Kansas City Monarchs in Chicago. “I called him over and introduced myself,” Sukeforth recalled to Rickey. “I asked if, during the practice, he would go to his right and throw the ball overhand with something on it; and to have somebody hit him balls over there. He said he would be very glad to, except for the fact that he was not playing. He said, ‘I fell on my shoulder several days ago and won't be able to play for probably a week.’ I then asked him if he would come down to the Stevens and meet me after the game…I made a date with Robinson to meet me at the Toledo park…I think I wired or telephoned you that I was bringing the player in, and you told me to go ahead.”

The August 24 telegram refers to Robinson twice as “player” because Rickey insisted on absolute secrecy. On August 28, 1945, as arranged by this telegram, Rickey and Robinson met for the first time, for three hours at Rickey’s 215 Montague Street office in Brooklyn. Rickey delivered the message that he wanted a player with enough guts not to fight back, and Robinson signed a—now lost—contract that Rickey dictated on the spot rather than the typical uniform contract that all players signed.

The second telegram was sent by Rickey that morning. “Plans changed,” it reads. Rickey had likely decided to ask Robinson to sign an unusual contract that day, requiring Sukeforth to call ahead because he was to be the contract’s counterparty. By signing what Rickey later called an “acceptance of terms” with Sukeforth rather than a standard contract with the Montreal Royals, Rickey would lock Robinson up without having to widen the circle of who knew about the great experiment. The other way in which plans had changed was that Sukeforth had been told only that Robinson might sign with Rickey’s Brooklyn Brown Dodgers. Sukeforth suspected, but had no way to know until the 28th, that plans had changed in that Robinson was wanted for the Dodgers.

LINK to a scene of the August 28 meeting from the movie 42.

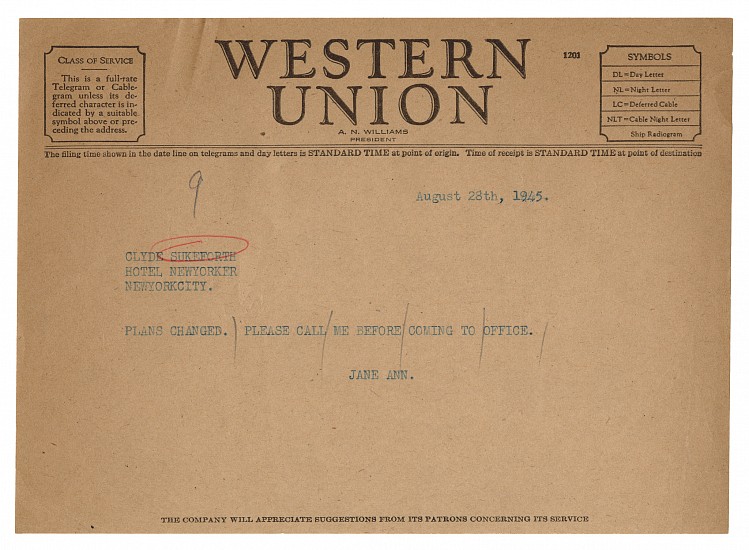

Telegram from Branch Rickey To Clyde Sukeforth, the morning of the first meeting between Rickey and Robinson, August 28, 1945

Ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 8 in. (14.6 x 20.3 cm)

Provenance: Branch Rickey; by descent to his grandson.

8508

It would be difficult to overstate the historical significance of these two telegrams (see previous object), as they are the only surviving objects related directly to the events of August 1945. The first establishes that contact with Robinson had been made by the Dodgers organization and arranged for the historic meeting between Robinson and Rickey; the best explanation for the second is that it sets forth a plan to get Robinson to sign his color-line crossing contract that day.

On August 24, 1945, Sukeforth made first contact with Robinson while he was with the Kansas City Monarchs in Chicago. “I called him over and introduced myself,” Sukeforth recalled to Rickey. “I asked if, during the practice, he would go to his right and throw the ball overhand with something on it; and to have somebody hit him balls over there. He said he would be very glad to, except for the fact that he was not playing. He said, ‘I fell on my shoulder several days ago and won't be able to play for probably a week.’ I then asked him if he would come down to the Stevens and meet me after the game…I made a date with Robinson to meet me at the Toledo park…I think I wired or telephoned you that I was bringing the player in, and you told me to go ahead.”

The August 24 telegram refers to Robinson twice as “player” because Rickey insisted on absolute secrecy. On August 28, 1945, as arranged by this telegram, Rickey and Robinson met for the first time, for three hours at Rickey’s 215 Montague Street office in Brooklyn. Rickey delivered the message that he wanted a player with enough guts not to fight back, and Robinson signed a—now lost—contract that Rickey dictated on the spot rather than the typical uniform contract that all players signed.

The second telegram [this one] was sent by Rickey that morning through Rickey's secretary, Jane Ann Jones. “Plans changed,” it reads. Rickey had likely decided to ask Robinson to sign an unusual contract that day, requiring Sukeforth to call ahead because he was to be the contract’s counterparty. By signing what Rickey later called an “acceptance of terms” with Sukeforth rather than a standard contract with the Montreal Royals, Rickey would lock Robinson up without having to widen the circle of who knew about the great experiment. The other way in which plans had changed was that Sukeforth had been told only that Robinson might sign with Rickey’s Brooklyn Brown Dodgers. Sukeforth suspected, but had no way to know until the 28th, that plans had changed in that Robinson was wanted for the Dodgers.

LINK to a scene of the August 28 meeting from the movie 42.

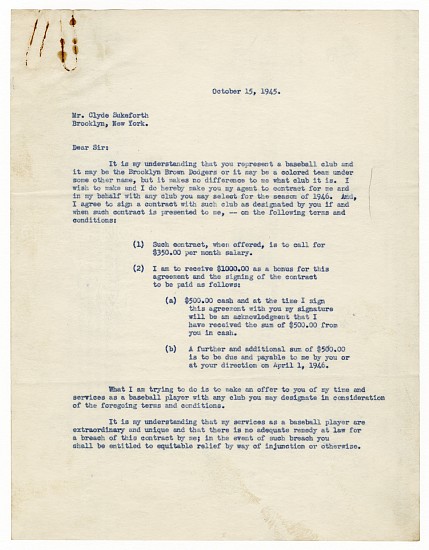

Don Newcombe's contract and supporting notes, October 15, 1945

Ink on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

6 sheets of paper, sizes down to 5 1/2 x 8 in.

Provenance: Branch Rickey; by descent to his grandson.

8512

This is the earliest known color line-crossing contract.

This contract, signed by Don Newcombe eight days before Jackie Robinson signed with Montreal, was likely the second color line-crossing contract, but it is the earliest one to survive.

Branch Rickey had two competing objectives: to sign as many talented black players as he could before other teams did so, and to maintain the secrecy of the entire project. His original plan was to sign several players—Robinson, Newcombe, Campanella, Wright, Partlow, and others—and announce them all at once. Having each player sign with a Dodgers affiliate, whether the Montreal Royals or the Nashua or Danville Dodgers, would have required widening the circle of those with knowledge of Rickey’s plans. To provide a cover story in the event his too-evident interest in black players was revealed, Rickey formed a black club called the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, though none of the men Rickey signed ever joined that roster.

In this contract, Newcombe signs with Sukeforth, who will contract on Newcombe’s behalf “with any club,” including the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, but it is quite clear from the language that Rickey and Sukeforth wanted the contract to be broad enough to anticipate a white club.

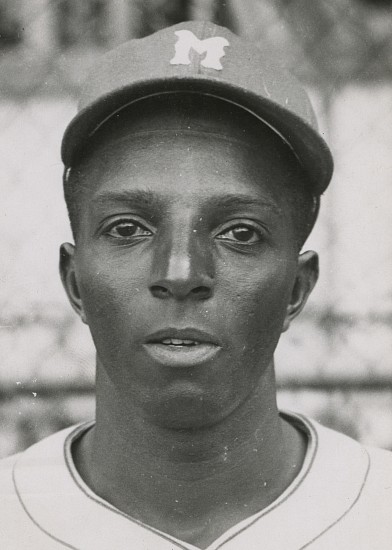

Unidentified photographer, Johnny Wright, 1946

Vintage gelatin silver print, 3 5/8 x 2 5/8 in. (9.2 x 6.7 cm)

Titled with numerical notation in pencil on print verso.

8476

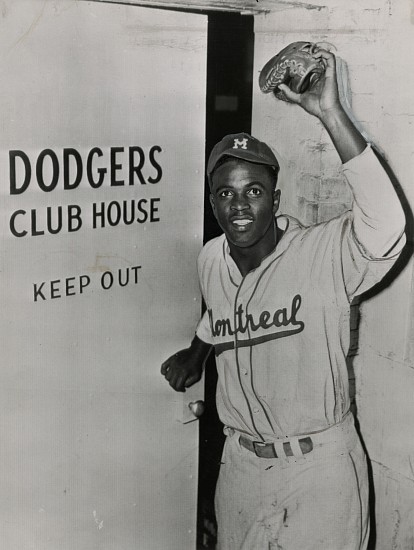

Johnny Wright was Jackie Robinson's roommate at the Dodgers' minor league affiliate, the Montreal Royals. He never made it to the Dodgers, but he did cross the color line.

Of the men who crossed, none had it harder than the pitchers. Johnny Wright, Roy Partlow, and Dan Bankhead—pitchers all—had particular difficulties with the added pressure.

Robinson explained: “John had all the ability in the world. But John couldn’t stand the pressure of being one of the first…If he had come in two or three years later when the pressure was off, John could have made it in the Major Leagues.”

Reflecting on the great experiment, Branch Rickey spoke of the “guts” necessary to effect change, and Wright’s struggle no doubt made a difference for others. As Wright said in February 1946, “There’ll be more and more colored boys in professional sports. I got this far by plugging, and I expect to keep on punching. That's all it takes.”

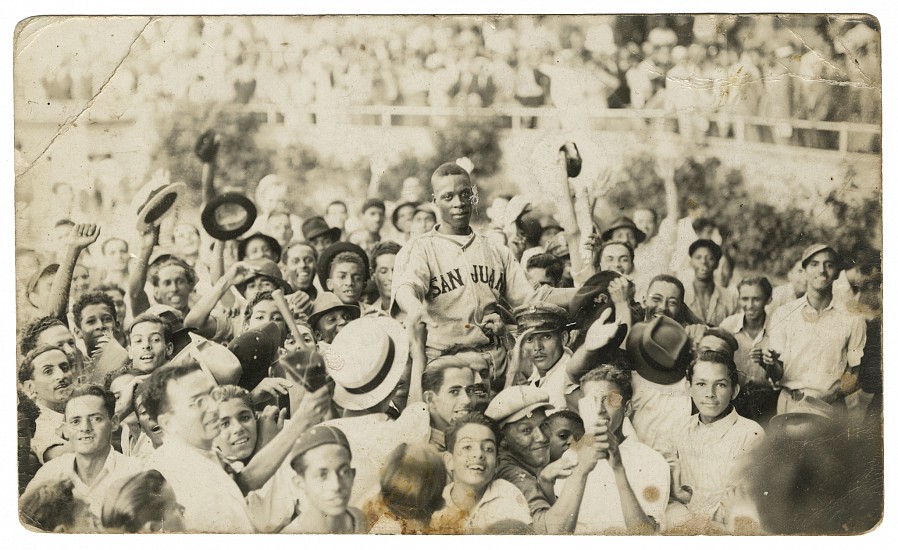

Unidentified photographer, Roy Partlow after defeating Satchel Paige, San Juan, December 23, 1939

Vintage gelatin silver print, 3 1/8 x 5 1/4 in. (7.9 x 13.3 cm)

Printed on postcard stock.

8477

Roy Partlow replaced Johnny Wright as Robinson’s roommate in Montreal but, like Wright, failed to make it to Major League Baseball.

His posture in negotiations with the Dodgers, including showing up late for spring training, drew rebuke from Robinson. His behavior, together with what the Pittsburgh Courier described as "a tendency to choke up while laboring among the caucasians" led to his release.

This image of Partlow is arguably the greatest image of triumph ever taken in the Negro Leagues. Partlow is carried on the shoulders of fans after defeating Satchel Paige in the Puerto Rican winter league.

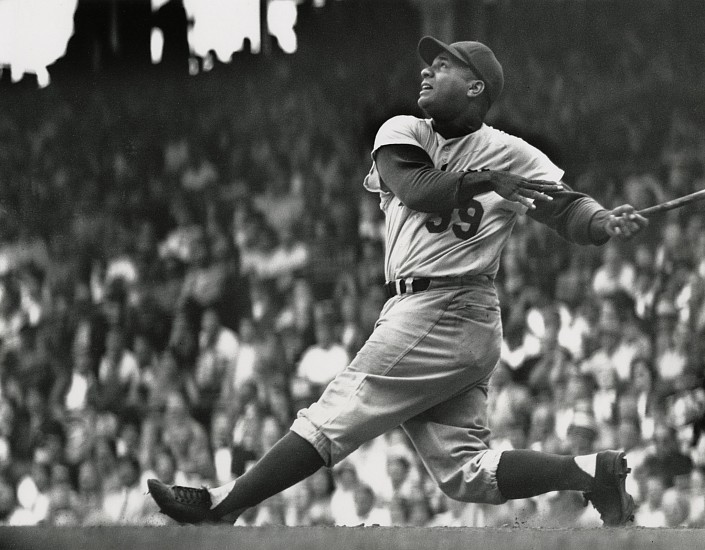

Robert Riger, Batting sixth and catching, No. 39: Roy Campanella (Brooklyn Dodger Line Up), 1955

Gelatin silver print; printed later, 10 5/8 x 13 11/16 in. (27 x 34.8 cm)

Mounted to 16 x 20 in. 2 ply mat board.

Titled in pencil on mount recto and verso in unknown hand.

8507

Martin Luther King Jr. famously remarked that his job was made easier by Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, and Roy Campanella. Robinson, however, was not particularly close with the other two men and there were occasionally very sharp differences of opinion on how to fight racism. For example, when a St. Louis hotel that had previously discriminated against them finally relented, Campanella and Newcombe chose to stay at the segregated hotel, to reward the proprietor who they felt had been good to them for years. Robinson, however, argued it was their duty to integrate the white hotel. “I’m no crusader,” Campanella replied. “I’m a ball player.”

Campanella was the sixth black player to appear in the Major Leagues. He won the Most Valuable Player award a year after Robinson and went on to win it a total of three times. Later he was elected to the Hall of Fame, also after Robinson. His career was cut short by the color line, which delayed his debut until he was 26, and then by a tragic car accident, which rendered him a quadriplegic.

Unidentified photographer, Effa Manley and "Mule" Suttles, 1938

Vintage gelatin silver print, 9 5/8 x 7 7/16 in. (24.4 x 18.9 cm)

with handwork

"Effa Manley/owner of Newark Eagles" and notations in pencil on print verso.

8483

Effa Manley was co-owner of the Newark Eagles, the team that produced Don Newcombe, Larry Doby, and George “Mule” Suttles, shown here “teaching” Manley something she obviously knew—how to hold a bat. Manley was a complex and assertive figure who worked for civil rights and also very publicly castigated Jackie Robinson for disparaging the Negro Leagues and Branch Rickey for failing to pay teams like the Eagles for their star players.

When Branch Rickey signed Don Newcombe of the Newark Eagles, Effa Manley wrote to him seeking compensation under Newcombe's contract, which may have contained a clause reserving his services for the following season, and was ignored. She also confronted Rickey in person.

Robinson added insult to injury in 1948 when he wrote an article for Ebony magazine titled “What’s Wrong with Negro Baseball.” Robinson's attack angered some, particularly Manley, who responded in an essay for Our World magazine: "I charge Jackie Robinson with being ungrateful and—more likely—stupid. Jackie Robinson is where he is today because of organized Negro baseball...He says Branch Rickey was fair and democratic. How much did Rickey pay the Kansas City Monarchs for Robinson? The answer? Zero. At this moment, the livelihoods, the careers, the families of 400 Negro ballplayers are in jeopardy because four players have been successful in getting into the major leagues."

Manley was the first woman elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

She kept a copy of this photograph in her scrapbook.

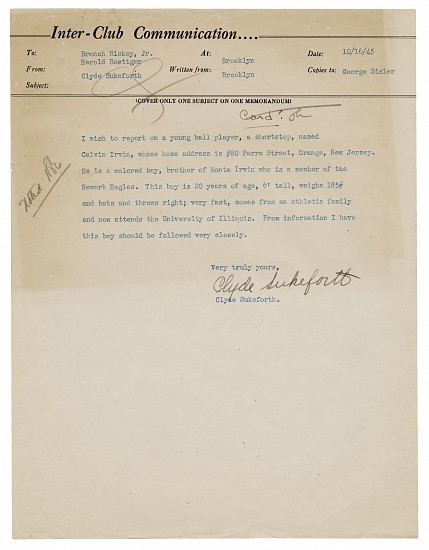

Calvin Irvin Scouting Report by Clyde Sukeforth, sent to Branch Rickey, October 16, 1945

Ink on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

8514

This scouting report, dated one day after Don Newcombe signed his acceptance of terms, focuses on Monte Irvin’s brother, Calvin. Calvin played part of the 1946 season with Effa Manley’s Newark Eagles, who had just defeated the Monarchs to win the Negro World Series. At shortstop, Calvin formed a double-play combination with Larry Doby, who would later become the second black man in the Major Leagues. The report sheds light on Branch Rickey, Sr.'s efforts to capitalize on his first-mover advantage, while also hinting at Manley’s vulnerability. Bill Veeck, owner of the Cleveland Indians, was Rickey's only competition at first.

As jarring as it sounds today, though the scouting report refers to Calvin as a "colored boy," the phrase was not intended to insult. Rickey, then 63, referred to all of his players as "boys" and continued to use those words until his death.

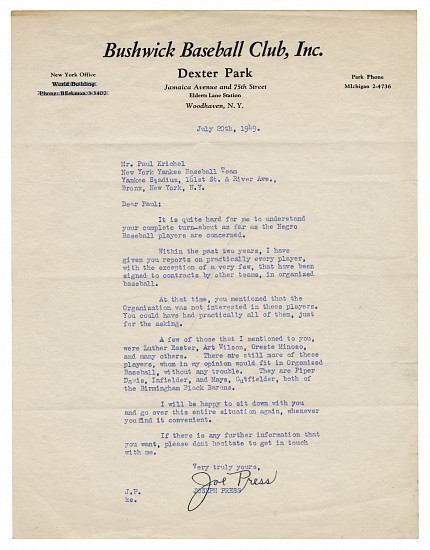

Letter from Joe Press to Paul Krichell, July 20, 1949

Ink on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

8511

This letter to Paul Krichell, who had discovered Lou Gehrig and was now head scout for the New York Yankees, indicates that the Yankees could have had almost any Negro League player they wanted—including Willie Mays—but that they had a policy of excluding them. Prior to the discovery of this letter, it was possible to argue that the Yankees’ slowness in signing black players was due to complacency, possibly because they won World Series titles in 1947 and 1949, had DiMaggio in center field, and had just signed Mickey Mantle to the Independence Yankees.

Joe Press, manager of the Brooklyn Bushwicks, who fielded multi-ethnic rosters and played exhibition games against Negro League teams, was well-placed to observe the talent of black stars and report his findings to Krichell. The policy change Press alludes to permitted the Yankees to draft Elston Howard in 1950; he would join the Yankees as their first black player in 1955.

The letter also sheds light on efforts by people whose names are forgotten to break down racial barriers in baseball.

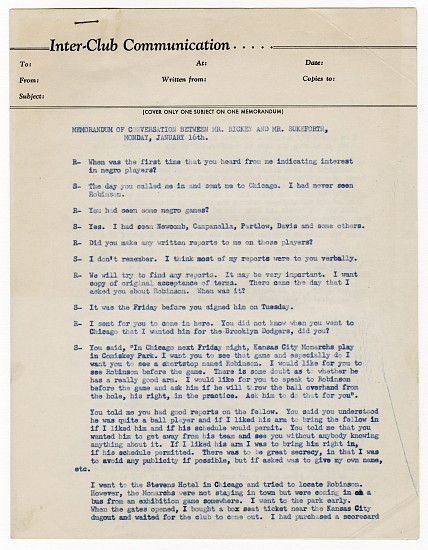

Transcript of Conversation between Branch Rickey and Clyde Sukeforth recounting events of August 28, 1945, and Robinson's first day as a Dodger, January 16, 1946

Ink on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

5 pages, stapled

Provenance: Branch Rickey; by descent to his grandson.

8513

In this conversation, Rickey has Clyde Sukeforth recount for the record the events that led to Robinson's signing, particularly Sukeforth's first meeting with Robinson and Rickey's historic meeting with both men on August 28, 1945. The scene was re-enacted by Harrison Ford and Chadwick Boseman in the movie 42. [See link below]

Rickey and Sukeforth also discuss allegations that Robinson faced discrimination from the Dodgers on his first day, particularly that his jersey was hanging from a nail and that Robinson had no locker. This is what happened, also as depicted in the movie 42, but as Sukeforth describes, it may not have been uncommon for rookies.

LINK to a scene of the August 28 meeting from the movie 42.

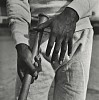

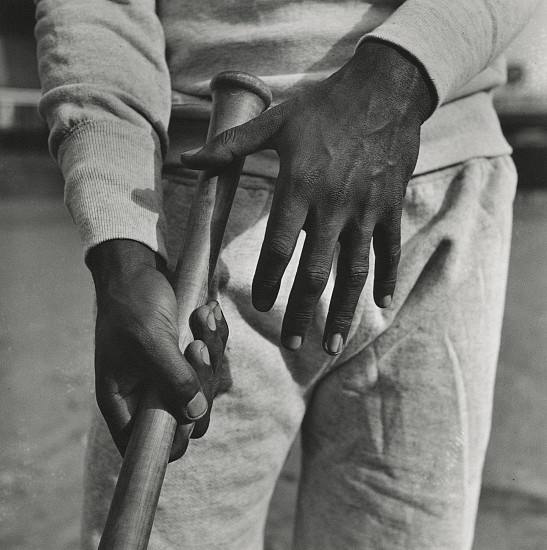

Harold Carter, Jackie Robinson's Hands, 1945

Gelatin silver print, 9 7/8 x 9 7/8 in. (25.1 x 25.1 cm)

"A" in pencil on print verso.

Illustrated: Life, November 26, 1945, p. 134.

8499

Jackie Robinson signed a contract to play for a Dodgers farm team, the Montreal Royals of the International League, on October 23, 1945, and Life quickly arranged for his first photographic feature. Beginning with this session, Robinson was photographed heroically throughout his baseball career—more consistently than any other player in the twentieth century, including Babe Ruth. This imagery was employed even before Robinson had accomplished anything on the field. As another Life photographer would later note about the Mercury astronauts, the mere act of being chosen was enough.

Life photographer Harold Carter met Robinson at Ebbets Field, although Robinson would not play there for another 17 months. Carter could have photographed Robinson's batting grip, as other Life photographers had done with Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams, but he made a conscious decision not to, instead showing Robinson about to take the bat in his hands as he prepares to start baseball's "great experiment." Using Robinson's own sweatshirt and pants as a graphic device to highlight his skin, the result is a portrait at least as interesting as any traditional photograph of a face.

LINK to Life, November 26, 1945, pp. 133-4, 137, cover.

J. R. Eyerman, Men toss a black cat on the field, c. 1950

Vintage gelatin silver print, 8 3/4 x 10 1/2 in. (22.2 x 26.7 cm)

Descriptive title typed on verso, written in ink and typed archive labels, photographer's credit stamp, Time/Life credit and file stamps in ink and Time Inc, Picture Collection labels verso.

Illustrated: Life, May 8, 1950, p. 130. People, April 28, 1997. [using this print]

5730

Life photographer J.R. Eyerman was the still photographer on the set of The Jackie Robinson Story. It reenacts a scene that occurred in 1946 in Syracuse, when a rival player threw a black cat from the dugout onto the field as Jackie waited to hit: "Hey Jackie, there's your cousin." Jackie doubled to left, then scored on a single to center. As he passed the Syracuse dugout, he offered his own taunt: "I guess my cousin's pretty happy now." Sometimes Robinson did fight, or at least push, back.

Robinson wrote that "the toll that incidents like these took was greater than I realized. I was overestimating my stamina and underestimating the beating I was taking. I couldn't sleep and often I couldn't eat."

LINK to Life, May 8, 1950, pp. 129-132, 135.

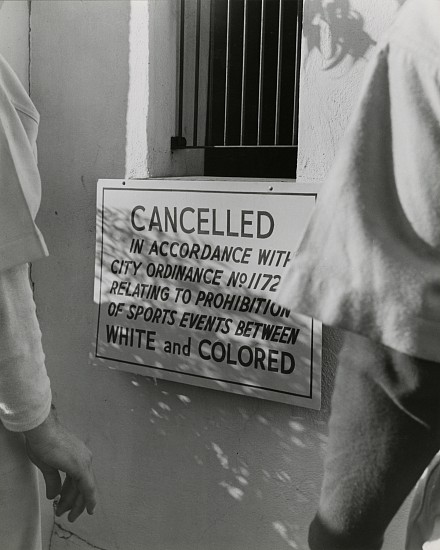

J. R. Eyerman, Cancelled-sports events between White and Colored, c. 1950

Vintage gelatin silver print, 9 1/4 x 7 1/2 in. (23.5 x 19.1 cm)

Descriptive title typed archive labels, photographer's credit stamp, Time/Life credit and file stamps in ink and Time Inc, Picture Collection labels verso.

5731

On March 17, 1946, in Daytona Beach, Florida, Jackie Robinson became the first black man in the 20th century to take the field alongside whites in a scheduled exhibition game for which admission was charged. Only four days later, however, word came that Jacksonville, a city that was about fifty percent black, forbade Robinson to play against a New York Giants farm club. When official notice arrived, Royals manager Clay Hopper canceled the game. A week later, Jacksonville canceled another Royals game, and followed by another, then Savannah, Georgia, and Richmond, Virginia, canceled as well.

Photographed on the set of The Jackie Robinson Story, this print was planned to be used by Time to illustrate the racist incident Robinson endured in 1946. However, we have been unable to find it illustrated in either Time or Life.

Baseball’s “great experiment” was so unquestionably just that we tend not to see how much Branch Rickey, the Dodgers organization, and sympathetic photographers acting on their own staged or controlled the content of images in order to increase the chances of success or polish legacies. The celebratory or triumphal nature of many of these images—and the rarity of images depicting players taunting Robinson or pitchers throwing at him—may color how this period is remembered today.

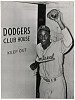

Unidentified photographer, Jackie Robinson, Rickey Opens the Door, April 11, 1947

Vintage gelatin silver print, 8 1/4 x 6 1/4 in. (21 x 15.9 cm)

Vintage copy print with handwork

Stamped with date "1947 APR 11 AM 11:18" by The Cleveland News and "Jackie Robinson" and other notations in red pencil on print verso.

Illustrated: Negro Heroes. National Urban League and Delta Sigma Theta sorority, Summer 1948. Comic book with original wrappers, last page.

8470

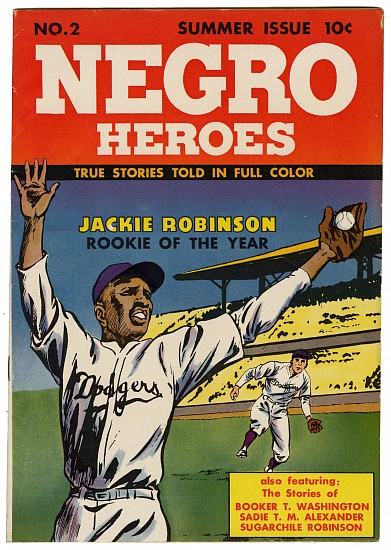

Jackie Robinson made his debut in a Brooklyn uniform on April 11, 1947. This image, shot by numerous photographers and obviously staged, was typically printed under the caption “Rickey Opens the Door.” The comic book, which includes an illustration of the same image, continues the theme of Robinson’s early heroization.

Negro Heroes, published by the National Urban League and Delta Sigma Theta sorority, sought to inspire children to cross all color lines. It wanted every child to know "about all jobs and have an equal chance to be trained and hired on whatever job for which he can qualify." "You too," it told readers, "can be among the heroes in American life."

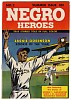

Negro Heroes, Summer, 1948

Comic book with original pictorial wrappers, 7 3/4 x 7 1/2 in. (19.7 x 19.1 cm)

Published by National Urban League and Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

8487

Negro Heroes sought to inspire children to cross all color lines. It wanted every child to know "about all jobs and have an equal chance to be trained and hired on whatever job for which he can qualify." "You too," it told readers, "can be among the heroes in American life."

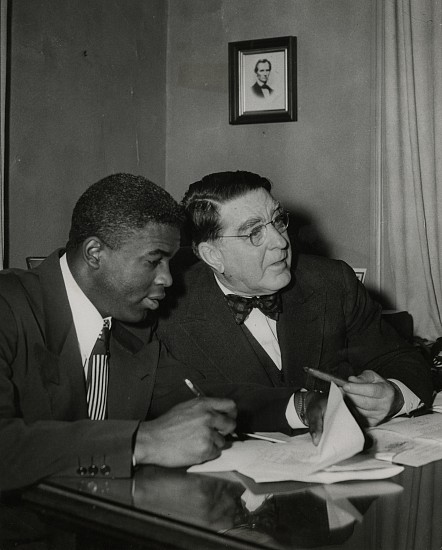

Unidentified photographer, Jackie Robinson signs his contract, January 24, 1950

Vintage gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 x 7 5/8 in. (24.1 x 19.4 cm)

Typed caption affixed to print verso with pencil notations and Keystone Pictures Inc. stamp on print verso.

8482

This photograph, taken during a contract signing, exemplifies Branch Rickey’s deliberate use of images and powerful symbolism in shaping the narrative of Jackie Robinson’s integration into Major League Baseball. For this photo opportunity, Rickey removed all the photographs on the walls except for the Lincoln portrait.

After the Dodgers first announced in 1945 that Robinson would be playing in Montreal, one of Branch Rickey's old enemies told the press: "We question Branch Rickey's statements that he is another Abraham Lincoln and that he has a heart as big as a watermelon and that he loves all mankind." As this photograph makes clear, Rickey liked the comparison and the symbolism the president's portrait provided as the backdrop to a contract signing photo opportunity. Rickey's admiration for Lincoln was real; so was his understanding of the power of images.

Rickey's office walls regularly displayed several images, as similar photographs of other contract signings make clear. The empty hook for a large frame can be seen above Robinson, and the frames themselves can be seen leaning against the wall.

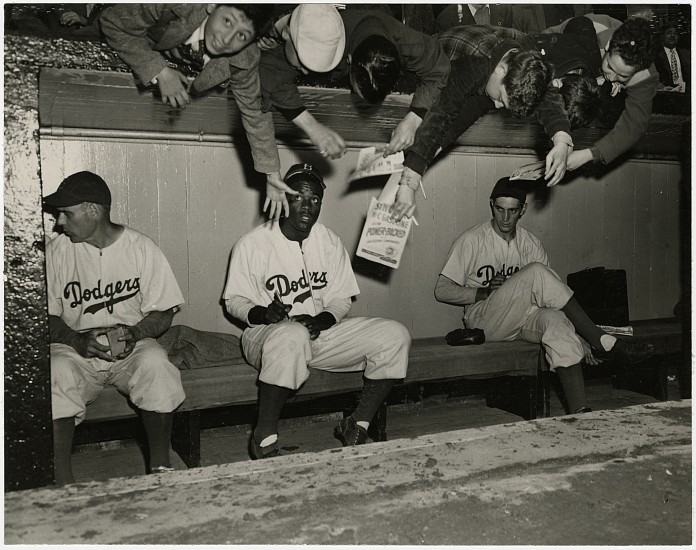

Unidentified photographer, Jackie Robinson signing autographs, c. April 11, 1947

Vintage gelatin silver print, 6 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (16.5 x 21 cm)

Later identification labels "Jackie Robinson on The Dodgers' bench early in the 1947 season. Coach Ray Blades is on the left, pitcher Ralph Branca on the right." on print verso.

8478

Robinson’s introduction to Major League Baseball was meticulously planned to include carefully controlled media to maximize the probability of success. On occasion, sympathetic photographers acting spontaneously helped the cause, as with this image in which children who were genuinely admiring of Robinson were asked to pretend to get his autograph. This was taken before a pre-season game that marked Robinson's first appearance in a Major League uniform.

Eddie Dweck, the boy at the far left reaching toward Robinson, recalled the scene 66 years later:

“We had maybe bleacher seats, the cheapest seats, and we were trying to get to the Dodger dugout just like we tried to get to the Dodger dugout every game we went. But there were a hundred photographers taking pictures of him. This was a momentous day. So they told the ushers ‘let these kids come down, and lean over like you’re trying to get his autograph.’ And that’s how we got down there. It was a matter of a few minutes, five minutes, ten minutes as I remember. Then we had to scatter. It looks like he’s signing something, but I don’t think anybody got an autograph, not while I was there."

Irving Haberman, Jackie Robinson crosses the Color Line (first day in the Major Leagues), April 15, 1947

Vintage gelatin silver print, 13 1/2 x 8 5/8 in. (34.3 x 21.9 cm)

Stamped with photographer's "Eyewitness Photos" stamp on print verso.

8500

Part of Rickey’s strategy was to attempt to reduce the extraordinary stress Robinson was under. Possibly as a result, he may have restricted photographers’ access, and only a few images of Robinson on Opening Day, 1947 exist.

Unidentified photographer, Jackie Robinson stands surrounded by eager autograph seekers, c. April 22-24, 1947

Gelatin silver print, 6 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. (16.5 x 21.6 cm)

Annotated "Jackie Robinson" in pencil and "Baseball File" in red pencil with International News Photos stamp and headline "Young Fans Besiege Their Hero" affixed to print verso.

Illustrated: The Chicago Star, April 26, 1947, p. 20 with the caption: "Jackie Robinson, first Negro to crash the Jim Crow barriers of major league baseball, stands surrounded by eager autograph seekers. As first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Jackie has already begun to show the form that made him the most valuable player in the International League last season."

8502

This image was made during the series against Philadelphia at Ebbets Field, the same series during which the Phillies viciously taunted Robinson. Yet the newspaper captions the photo so as only to mention "eager autograph seekers" and Robinson's promise on the field, an example of overlapping realities.

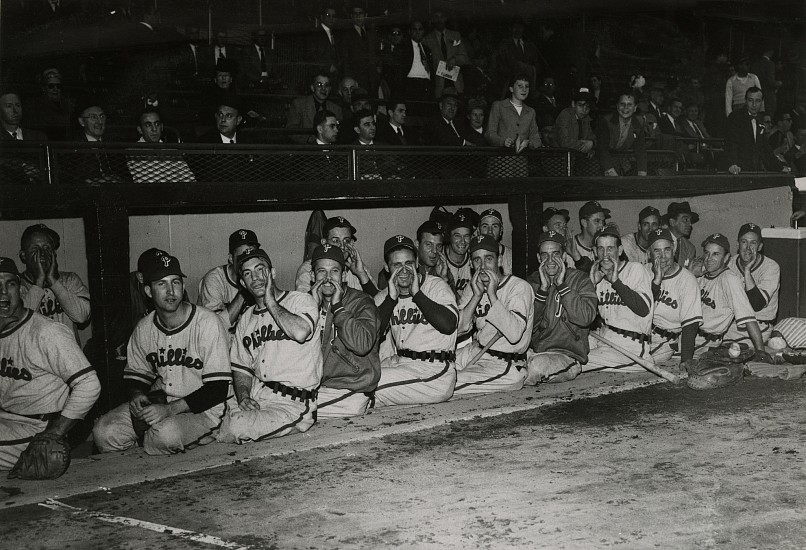

William C. Greene, Phillies dugout taunting Robinson, c. April 22, 1947

Vintage gelatin silver print, 6 7/16 x 9 5/8 in. (16.4 x 24.4 cm)

Dated 1947 and "(yelling at Jackie Robinson)" in ink and stamped "PHOTO BY/ WM. C. GREENE" with Sporting News Collection authentication label and "41" label and numbered "pau461" in pencil on print verso.

8479

This recently discovered photograph is the only known example of an image capturing the verbal abuse Robinson suffered on the field during his rookie year. Robinson said that this specific experience nearly broke him.

Members of the Phillies taunt Jackie Robinson or, possibly, gleefully reenact their taunting for a photographer. As Robinson would later write, Tuesday, April 22, 1947, "of all the unpleasant days in my life, brought me nearer to cracking up than I had ever been:

Starting to the plate in the first inning, I could scarcely believe my ears. Almost as if it had been synchronized by some master conductor, hate poured forth from the Phillies dugout.

'Hey, n*****, why don't you go back to the cotton field where you belong?'

'They're waiting for you in the jungles, black boy!'

'Hey, snowflake, which one of the white boys' wives are you dating tonight?'

'We don't want you here, n*****.'

'Go back to the bushes!'

Those insults and taunts were only samples of the torrent of abuse which poured out from the Phillies dugout that April day."

Unidentified photographer, Jackie Robinson returns an autograph to a fan in the stands. Dodgers' spring training in Cuidad Trujillo (now Santo Domingo), Dominican Republic, March 6, 1948

Gelatin silver print; printed later, 7 7/16 x 9 3/8 in. (18.9 x 23.8 cm)

Probably printed from a copy negative.

Annotated [incorrectly] "Jackie Robinson at Ebbett's Field" in ink with printing percentages and other annotations in red on print verso.

Illustrated: The St. Louis Star and Times, March 8, 1948.

8503

This is a rare image of Robinson with black fans, taken during spring training in the Dominican Republic. The enthusiasm for Robinson is palpable, and Branch Rickey had been concerned that this was only adding to the pressure. He therefore urged reporters to ask fans to treat Robinson like others and cheer only when he did something on the field that merited applause.

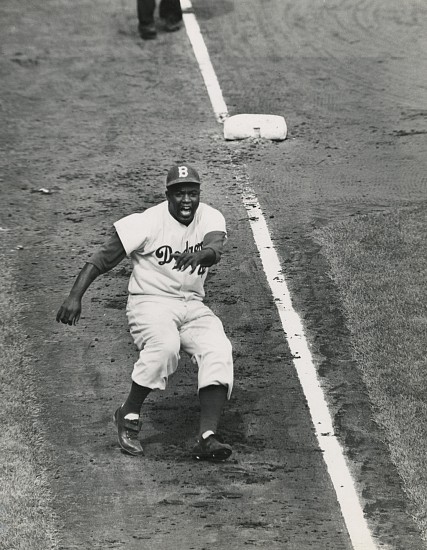

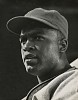

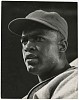

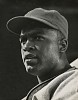

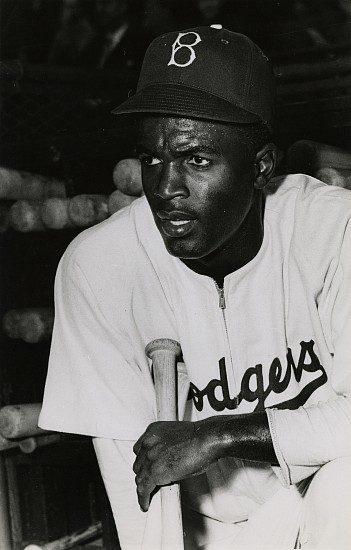

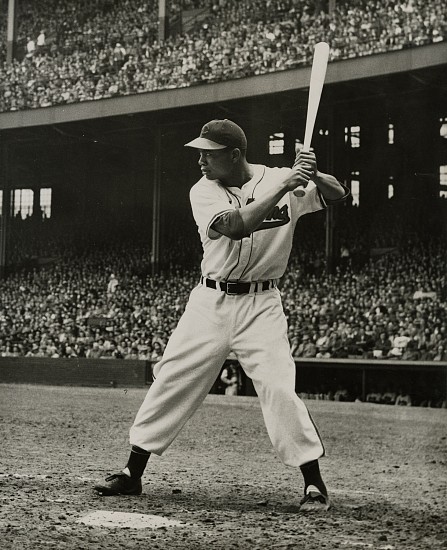

J. R. Eyerman, Jackie Robinson, 1950

Vintage gelatin silver print, 13 1/4 x 10 1/2 in. (33.7 x 26.7 cm)

Photographer's credit stamp, Time/Life credit and file stamps in ink and Time Inc, Picture Collection labels verso.

Illustrated: Life, May 8, 1950, cover [using this print]

5729

J.R. Eyerman’s low-angle photograph, during the filming of The Jackie Robinson Story, portrays Robinson as a heroic figure. This iconic image not only graced the cover of Life magazine but also became part of the US Postal Service’s Black Heritage stamp series in 1982.

LINK to Life, May 8, 1950 cover, pp. 129-132, 135.

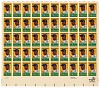

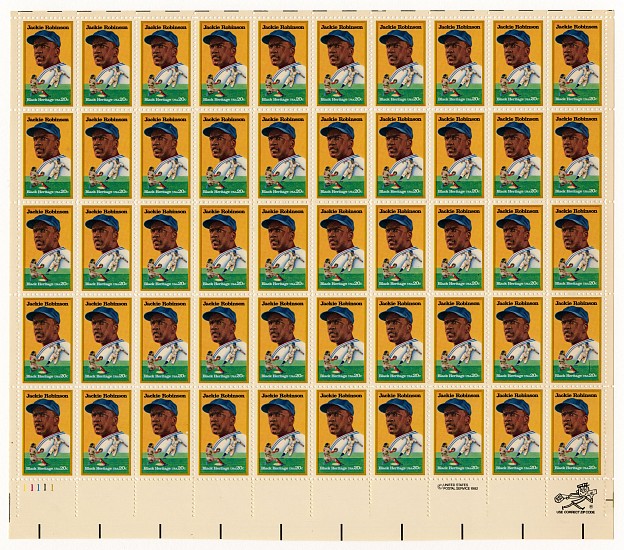

Jackie Robinson, US Postal Service Black Heritage Series postage stamps, 1982

Letterpress, 8 15/16 x 10 3/16 in. (22.7 x 25.9 cm)

a full pane

Reproducing the J.R. Eyerman photograph that was used originally on the cover of Life, May 8, 1950.

8516

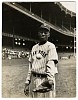

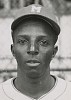

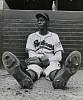

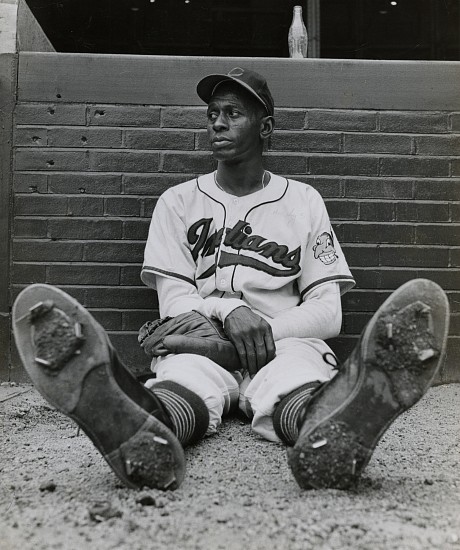

Arthur Alex Somers, Larry Doby, c. 1947-48

Early gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

Titled "Doby, Larry/Baseball" in ink and "Larry Doby-OF-Cleveland" in pencil with photographer's stamp and Houston Post April 2, 1959 stamp on print verso.

8552

Larry Doby had played for Effa Manley’s Newark Eagles prior to World War II, but during his service, with no path to Major League Baseball, he decided to become a teacher and coach. “But when I heard about Jackie,” Doby remembered, “I decided to concentrate on baseball.” He rejoined the Eagles after the war, capturing the attention of Cleveland owner Bill Veeck, who shared Branch Rickey’s interest in black players but not his parsimony: Veeck compensated Effa Manley for Doby’s contract.

Although Jackie Robinson gets almost all of the credit for integrating baseball—Robinson’s photographs outnumber Doby’s ten-to-one, even though Doby played in more games—the two men were subjected to similar ordeals, particularly because Doby began alone in the American League. “It was 11 weeks between the time Jackie Robinson and I came into the majors,” Doby recalled. “I can’t see how things were any different for me than they were for him.”

On his first day, two teammates refused to shake Doby’s hand. Fans, however, were more accepting: “As Doby emerged and started across the field to the Cleveland bench,” a sportswriter put it, “a few spectators saw him and applauded. With each step the chorus swelled until, as he approached the first base dugout, it had attained the proportions of an ovation. An uncommonly large proportion of the spectators were colored, but it was noticed that Negroes and whites alike joined in the greeting.”

Doby became a seven-time All-Star and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998.

This image was used as the basis for the illustration featured on Doby’s 1950 [included in the collection and pictured above] and 1951 baseball cards made by the Bowman Gum Company.

I'm for Larry Doby, c. 1947

Pennant

8549

Larry Doby was the second black player to cross the color line, making his debut with the Cleveland Indians in July 1947, 11 weeks after Robinson joined the Dodgers. Despite the parallel significance of their achievements—Doby was all alone in the American League while Robinson was in the National League—his impact remains significantly overshadowed by Robinson's. Doby's accomplishments, however, were profound. A seven-time All-Star and the first black player to hit a home run in a World Series game, Doby was instrumental in challenging racial barriers.

Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck faced resistance from some players when integrating Larry Doby as the American League's first black player. Veeck acknowledged economic concerns among players but emphasized the inevitability of racial integration in baseball, stating, "The entrance of Negroes into the majors is not only inevitable—it is here." Veeck initially expressed optimism about the pace of change, signing Doby with the reasoning that Robinson had proven himself as a skilled player. However, within two weeks, he tempered expectations, noting that only a limited number of worthy Negro League players remained. Surprisingly, Branch Rickey concurred with Veeck, expressing doubt that many black players would succeed. As historian Jules Tygiel has pointed out, however, Veeck and Rickey had scouting reports suggesting otherwise (see, for example, the October 1945 scouting report of Calvin Irvin). One explanation, consistent with Rickey's meticulous preparations for Robinson's integration, could be Rickey's awareness of Gunnar Myrdal's, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy. Myrdal wrote, “If Negro workers are introduced a few at a time, if they are carefully picked, if the leaders of the white workers are taken into confidence, and if the reasons for the action are explained, then the trouble can be minimized, and the new policy may eventually become successful.”

The pennant and pins were sold by vendors outside Ebbets Field and Cleveland Stadium to capitalize on the desire of fans to show their support for Robinson and Doby.

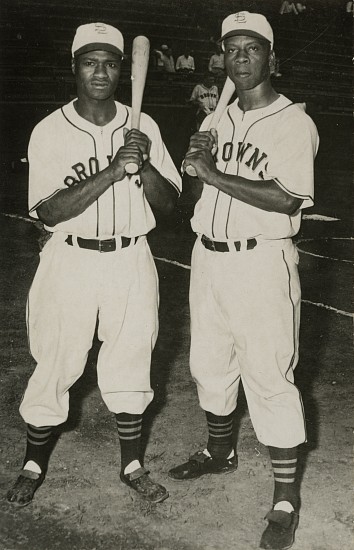

George Dorrill, Willard Brown and Hank Thompson, 1947

Vintage gelatin silver print, 5 3/8 x 3 1/2 in. (13.7 x 8.9 cm)

Titled "Hank Thompson + Willard Brown" in ink with "St. Louis Browns/Negro Stars" in pencil and photographer's label affixed with Page# 28 Key# 5/Job No. 8625/Camera Setting 5/5 with numbers written in ink.

Illustrated: The Sporting News, July 30, 1947.

8551

Willard Brown and Hank Thompson were the third and fourth men to cross the color line, and the first two to do so as teammates—the first to do so since Fleet and Weldy Walker were teammates on the 1884 Toledo Blue Stockings in the American Association. Unfortunately for them, they were signed by St. Louis, which was among the most difficult cities for black players. In this photograph, Brown and Thompson appear to be caught in the flashbulb’s glare, possibly overwhelmed. Although Thompson did well, Brown did not, and neither attracted fans as anticipated, leading the St. Louis Browns to dismiss them only one month after their appearance. Thompson later joined the New York Giants and played in the outfield with Willie Mays.

Fan letters saved by Dan Bankhead, Jackie Robinson's roommate and the first black pitcher, August-November, 1947

Ink on paper

53 letters and 13 postcards

8520

Dan Bankhead was the first black pitcher to join the Dodgers and Jackie Robinson's roommate. Despite high expectations, Bankhead did not succeed. Negro League great Buck O'Neill explained:

"See, here’s what I always heard. Dan was scared to death that he was going to hit a white boy with a pitch. He thought there might be some sort of riot if he did it. Dan was from Alabama just like [Satchel Paige]. But Satchel became a man of the world. Dan was always from Alabama....He heard all those people calling him names, making those threats, and he was scared. He’d seen black men get lynched."

The letters, all written during Bankhead's first days, are filled with hope, admiration, and advice. One fan addressed Bankhead's problem directly: "The trouble is that those few people who hate to see any Negro get ahead have such big mouths that there seem to be a lot of them. Remember that when you're on the mound."

George Silk, Satchel Paige, 1948

Vintage gelatin silver print, 12 3/4 x 10 5/8 in. (32.4 x 27 cm)

Title, date and credit on typed label with credit stamps in ink verso.

Illustrated: Decade of Triumphs: The 40s (Our American Century series). Time Life, 1999, p. 177.

5732

This iconic photograph symbolizes Satchel Paige’s long-awaited breakthrough into Major League Baseball. The old Cleveland uniform, however, is a reminder that Baseball had more work to do. An example of the patch from 1947-1950, is also included in the collection. [See secondary image]

"Satch' Makes the Majors," declared Life in July 1948. The magazine ran a variation of this image with the caption: "Paige loves rest and after a workout likes to flop and watch his teammates drill, extending the mighty feet that helped earn him his nickname. As a free-lance pitcher Paige made about $30,000 a season. His possessions now include four fancy cars, five hunting dogs and more than 20 expensive shotguns."

Photographer George Silk dramatically foreshortened Paige to exaggerate the size of his feet, which the public believed were the source of his nickname. "My feet ain't got nothing to do with my nickname," Paige explained, "but when folks get it in their heads that a feller's got big feet, soon the feet start looking big."

According to Paige’s biographer Larry Tye, the full story of how Leroy Robert Paige became Satchel Paige is as follows:

All the Paige kids knew by the age of six that they had to help to put food on the table and, in a good year, shoes on their feet. Leroy worked the alleyways like a pro, cashing in empty bottles he found there. Delivering ice also brought in small change. But he was springing up like a weed in a bog, and as he grew so did Lula’s and John’s expectations of his earning power. The obvious place to look for work was the nearby L&N station, where the pint-sized porter polished the boots of wealthy white travelers or carried their bags to hotels like Mobile’s luxurious Battle House for as little as a dime. Realizing he could not bring home a real day’s pay if he made just 10 cents at a time, he got a pole and some rope and jerry-rigged a contraption that let him sling together two, three, or four satchels and cart them all at once. His invention quadrupled his income. It also drew chuckles from the other baggage boys. “You look like a walking satchel tree,” one of them yelled. The description fit him to a tee and it stuck. “LeRoy Paige,” he said, “became no more and Satchel Paige took over.”

LINK to Larry Tye’s full article.

This is a story about four handshakes—the most common motif photographers used to communicate Jackie Robinson’s acceptance in white baseball. There is a perspective on America in this group of images—its ideals, its inevitable problems, and its rare ability to solve them, always provisionally.

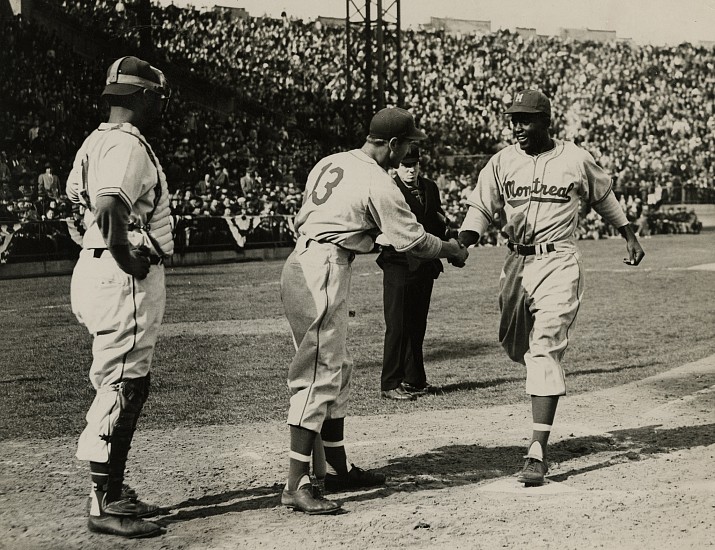

Frank Jurkoski, Shuba shakes hands with Robinson after his first home run, April 18, 1946

Vintage gelatin silver print, 6 1/16 x 7 7/8 in. (15.4 x 20 cm)

With original caption typed on paper 4 x 6 3/16 in.

"S-1039715-WATCH YOUR CREDIT..INTERNATIONAL NEWS PHOTO/ SLUG..(ROBINSON SCORES)/ ROBINSON HOMERS IN AAA LEAGUE DEBUT/ JERSEY CITY, N.J....JACKIE ROBINSON, NEGRO SECOND/ BASEMAN WHO MADE HIS AAA LEAGUE DEBUT WITH THE MONTREAL/ ROYALS, TODAY IS SHOWN BEING CONGRATULATED BY THE NEXT/ BATTER, SHUBA, AFTER SMASHING A THREE RUN HOMER IN THE/ THIRD INNING AGAINST THE JERSEY CITY GIANTS AT ROOSEVELT STADIUM, ROCKLEY AND DE FORGE SCORED AHEAD OF ROBINSON/ ON THE CIRCUT CLOUT. MONTREAL WON 14-1./ B-4-18-46 PHOTO BY FRANK JURKOSKI NY R"

8475

This photograph was taken for the Associated Press on April 18, 1946, when Robinson made his debut with the Montreal Royals on Opening Day. In the third inning, Robinson hit a three-run homer over the left field fence. As he leapt for home plate, George Shuba, the Royals' left fielder and their next batter, shook his hand.

This image was little commented on then, but its meaning has grown over time, and it endures today as a portrait of racial tolerance. So much so that, more recently, it was cast as a monumental bronze statue.

Tom Watson, Jackie Robinson's first Major League home run, April 18, 1947

Vintage gelatin silver print, 6 5/8 x 8 1/4 in. (16.8 x 21 cm)

Annotated "Robinson scoring" and numbered in pencil with International News Photo agency stamp on print verso.

Illustrated: Daily News, April 19, 1947, back cover.

8501

Jackie Robinson hit his first home run for the Dodgers on April 18, 1947. Tommy Tatum, the next batter, is seen shaking Robinson’s hand as he touches home. The image, its symbolism obvious to all, ran on the back cover of the Daily News the next day.

The image was used in 1998, shortly after Steve Jobs’s return to Apple, in the company’s “Think Different” marketing campaign, which contributed greatly to its endurance in American memory.

Tom Watson, Think Different, 1998

Poster, 35 15/16 x 23 15/16 in. (91.3 x 60.8 cm)

1998 Apple copyright with MLB permission printed in image upper right edge.

0502

The image was used in 1998, shortly after Steve Jobs’s return to Apple, in the company’s “Think Different” marketing campaign, which contributed greatly to its endurance in American memory.

It is a cropped image of Tom Watson's photograph for the Daily News of Jackie Robinson's first Major League home run, April 18, 1947.

As his right foot touched home, Tommy Tatum, the next batter, shook his hand. The image, its symbolism obvious to all, ran on the back cover of the Daily News the next day.

Unidentified photographer, Jackie Robinson and Ben Chapman, May 9, 1947

Vintage gelatin silver print, 8 1/2 x 7 in. (21.6 x 17.8 cm)

Vintage copy print with retouching.

Titled in pencil with International News Photos stamps on print verso.

8481

Only days after Robinson’s first home run with the Dodgers, he endured his most difficult day when the Phillies, led by Ben Chapman, viciously taunted him from their dugout.

On May 9, 1947, when Robinson was playing in Philadelphia, baseball’s commissioner forced Chapman to make a public display of conciliation. Although Chapman would not shake hands, the public accepted this image as evidence an accommodation had been reached.

Freddy Schmidt, who played for Chapman and disliked him, recalled the reality of the scene: "I never talked to [Robinson] but he came over to our dugout after what went on the night before...Chapman was standing on the top step, and he was holding a bat, and they wanted to get Jackie over to smooth things over. And he says, 'You know, Jackie? Good ballplayer, but you're still a n***** to me.'"

Barney Stein, Robinson and Reese hold hands, April 15, 1954

Gelatin silver print; printed later, 9 9/16 x 7 9/16 in. (24.3 x 19.2 cm)

Resin coated print. Photographer's stamps and address with typed caption taped to print verso. Caption reads, "From Barney Stein/Here's an action shot one will seldom/ see in baseball as Jackie Robinson and/ Captain Pee Wee Reese hold hands on/ [after] crossing the plate on/ Jacki[e] Robinson'/ homer. Dodgers' bat boy Joey [sic; Charlie] Di Giovanna/ walks behind them as he carries Jackie's/ bat."

8504

This image of Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese holding hands conveys a profound sense of affection beyond mere acceptance.

The story of how Pee Wee Reese put his arm around rookie Jackie Robinson on the field during a difficult day, demonstrating to all his support, has entered legend. It is likely, however, that Robinson misremembered it—no writer even mentioned it—and that it may have happened later, or not at all. The story nevertheless contained a truth Robinson wanted to tell.

Barney Stein described this image in a typewritten caption as something more than a handshake. Robinson and Reese, he wrote, “hold hands.” While other images communicate acceptance or even friendship, this one conveys something more—namely, affection.

This group of objects was curated to substantiate the persistence of problems well after Jackie Robinson crossed the color line, as any reasonable person then would have expected, but as we sometimes forget. The success of the “great experiment” in racial integration was never assured and, as Branch Rickey so eloquently put it in his notes, it required both “devotion to purpose” and enormous courage. Problems are, of course, inevitable and no solution final. That is why Ralph Morse’s photograph has the last word, depicting Jackie dancing provocatively off third, always pushing toward home.

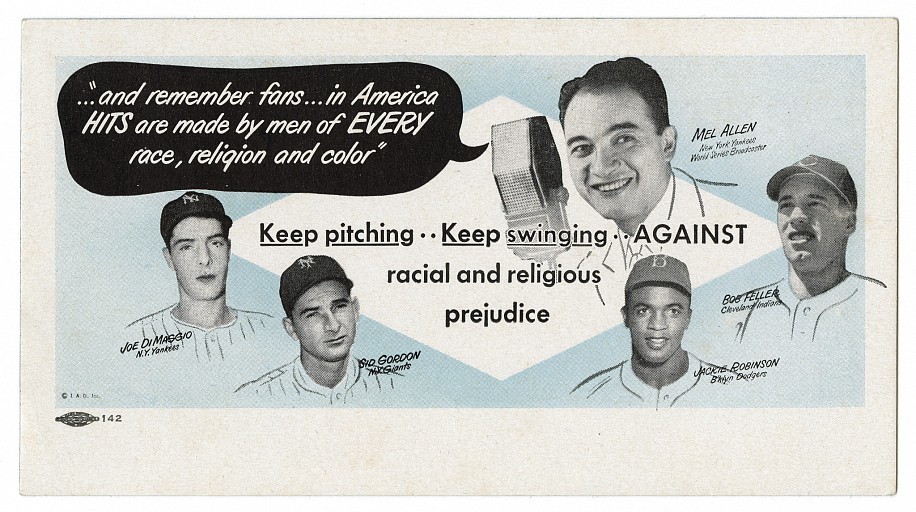

Baseball Fights Prejudice, 1948

Ink on paper; flexography, 3 3/8 x 6 3/16 in. (8.6 x 15.7 cm)

The Institute for American Democracy, Inc.

backed with blue card stock

8510

This blotter was described contemporaneously in an article titled Baseball Fights Prejudice as follows:

“The Institute for American Democracy, Inc., has adopted a baseball theme for its next car-card and blotter campaign against discrimination. In the picture, Mel Allen, sports announcer, is at a broadcasting mike, saying 'Remember fans, here in America hits are made by men of every race, religion and color.' Inside the white infield are the words, 'Keep pitching! Keep swinging against racial and religious prejudice!' The striking poster is complete with the head pictures of Joe DiMaggio, Sid Gordon, Jackie Robinson and Bobby Feller. Baseball can take a well-earned bow for helping the Institute for American Democracy, Inc., carry on its work of national unity, especially among the youth of the nation. The youngsters of today must be brought up to respect the rights of their fellow men, regardless of color or religion.”

Eastman Dodgers admission tickets, colored section and white section tickets, c. 1948-1953

3 tickets including rain check

Each 2 x 2 1/16 in. (5.1 x 5.2 cm.)

8484

More than six years after Jackie Robinson had crossed the color line, only six of Major League Baseball's teams had integrated. Segregation remained lawful, and the Eastman Dodgers, a minor league club in Georgia unaffiliated with the Brooklyn Dodgers, still sold separate tickets to white and black fans.

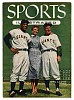

Hy Peskin, Willie Mays, Laraine Day [Mrs. Leo Durocher], and Leo Durocher, March 2, 1955

2 color positive transparencies (diapositives), each 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inches (5.7 x 5.7 cm) and

2 modern pigment prints, each 4 x 4 inches (10.2 x 10.2 cm)

8485

This photograph, featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated on April 11, 1955, marked a historic moment as the first time a national magazine showcased a white woman and a black man touching.

As can be seen from these two images, Peskin had a version in which Mays and Laraine Day were not next to each other. Editors would later recall they did not consider the possibility some might react negatively to an image of a white woman with her arm around a black man.

Some readers reacted very negatively, revealing the deep-seated racial tensions of the time. A reader from Nashville wrote: "To tell you that I was shocked at SI's cover would be putting it mildly...The informative note inside the magazine tells me that this is Mrs. Leo Durocher, a white woman, with her arm affectionately around the neck of Willie Mays, a Negro ballplayer...Let me say to you, Sir, the most appalling blow ever struck this country, the most disastrous thing that ever happened to the people of America, was the recent decision of the Supreme Court declaring segregation unconstitutional."

Responding to that letter and others, a reader from Long Beach, New York, wrote: “I was disgusted at the letters concerning the cover of Willie Mays and Mrs. Leo Durocher. I may be only 15 years old but I have more common sense than any adult with those ideas.”

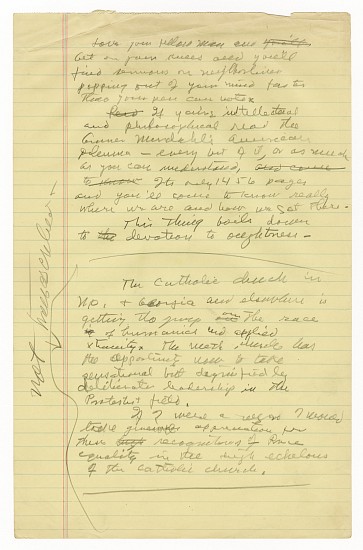

Branch Rickey's personal notes, possibly for the speech he gave on November 13, 1965, at the Daniel Boone Hotel, Columbia, Missouri, during which he suffered a stroke; he never regained consciousness, c. 1965

Graphite and ink on paper, 13 1/4 x 8 1/2 in. (33.7 x 21.6 cm)

6 sheets

8515

These handwritten notes were drafted near the end of Branch Rickey’s life. The contents overlap closely with the speech Rickey was giving when he suffered a stroke, never to regain consciousness and may be preparatory.

Rickey writes about the influence of Zaccheus, from the Gospel of Luke, and of Giovanni Papini’s Life of Christ (1923), from which he read to Robinson during their first meeting, to make sure Robinson understood the importance of turning the other cheek.

Rickey also writes of Gunnar Myrdal’s monumental An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy (1944), which provided Rickey’s strategy of picking black players carefully, introducing them a few at a time, taking the leaders of the white workers into confidence, and explaining the reasons for the action.

Moving back and forth between religious principles and Myrdal’s philosophical and practical arguments, Rickey concludes, “This thing boils down to devotion to oughtness.” In the margin, he adds, “It is difficult to understand how anyone can reconcile the teachings of Christ with the denial of moral responsibility to human beings of a different race or origin.”

Finally, Rickey turns to courage. The idea is “explosive—instant, uncompromising—never falters under adverse surprise—can be possessed by election, can abide and be permanent...It shows itself without thinking—it counts no credit for its cumulative score. One does not know he has it. It is the visible show of paying without asking the price.”

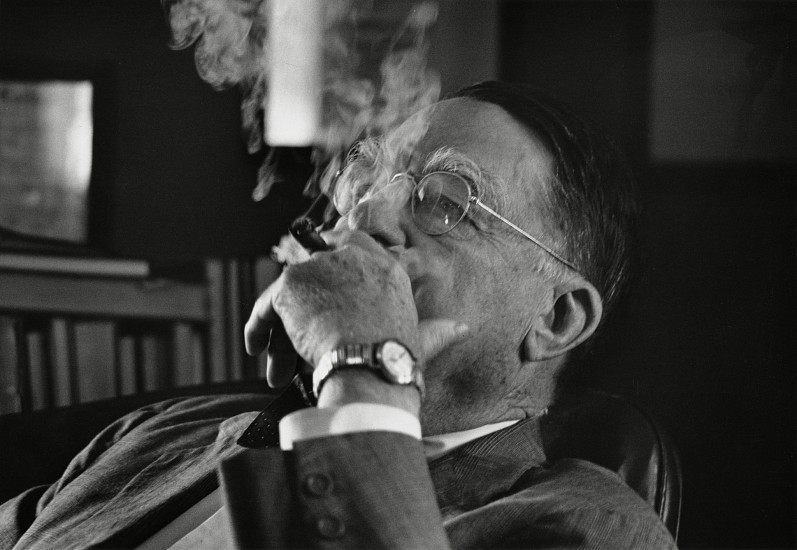

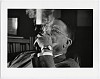

Robert Riger, Branch Rickey, 1965

Gelatin silver print; printed later, 8 3/8 x 12 1/8 in. (21.3 x 30.8 cm)